|

|

Left: A Renaissance-era lute. Unlike a watch, a lute does not do anything unless a human being is playing it. For this reason, Professor William Dembski, a leading proponent of Intelligent Design, thinks that the lute is a much better metaphor for the world than a watch.

Right: Painter David Hoyer playing a lute by Jan Kupecky (1667-1740). Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

It is an open secret that many Intelligent Design proponents don't particularly like the watch metaphor, and I’m somewhat surprised that Feser appears to be unaware of this. For instance, as far back as 2004, Professor William Dembski, a leading Intelligent Design proponent, wrote an article entitled, Intelligent Design: Yesterday's Orthodoxy, Today's Heresy, in which he made the following comments about the watch metaphor:

I am a much bigger fan of the Church Fathers than I am of William Paley. I like Paley and think he has a lot of good insights. But I think the watch metaphor was in many ways unfortunate. It is faulty, because the world is not like a watch.The Church Fathers did not use the watch. Instead, they spoke about a musical instrument. Gregory of Nazianzus, I think in his second theological oration, makes a design argument which is virtually parallel to William Paley's, except in place of a watch he has a lute. The lute maker makes the lute, but that is not all. The lute maker is then also interested in playing the lute.

This has huge implications, because it is entirely appropriate to play, or interact with, a lute after it has been created. That is why I think this is a much better metaphor than that of the watch. As Christians, we believe that God is not an absentee landlord. God creates the world but then he also interacts with it.

The watch metaphor is the type of metaphor that we get from a mechanical philosophy, where things work automatically, one thing bumping into another as chain reactions, with things working themselves out. If you have a perfect watch that keeps perfect time and never needs winding, it will go on for ever. But with a lute, or with any musical instrument, you need a lute player; otherwise it is just sitting there. In fact, it is incomplete without the lute player.

Catholic philosopher Jay Richards, who is also a well-known proponent of Intelligent Design, approvingly quotes this passage from Dembski in his book God and Evolution (Discover Institute Press, Seattle, 2010), in an essay entitled, "Understanding Intelligent Design."

If I read Professor Feser aright, however, he would object to the use of even the lute metaphor in a philosophical argument for the existence of God, on the grounds that a lute, like a watch, lacks immanent finality. As he himself put it in a recent post:

What is true of hammocks is from an A-T [Aristotelian-Thomistic] point of view true also of watches, cars, computers, houses, airplanes, telephones, cups, coats, beds, doorstops, and countless other things. Like the hammock, they are artifacts rather than true substances because their specifically watch-like, car-like, computer-like, etc. tendencies are extrinsic rather than immanent, the result of externally imposed accidental forms rather than substantial forms...[S]ince natural objects are (for the A-T philosopher) simply not artifacts in the relevant sense, it is a waste of time to argue for a divine designer on the basis of the assumption that they are... (Nature vs. art, 30 April 2011)

It should be clear from the above quote that Professor Feser would reject the use of any material artifact serving as a metaphor for the natural world, in a rigorous philosophical argument for the existence of God.

I would actually agree with Feser that it is impossible to construct an adequate metaphor for a natural object, for the simple reason that the only kinds of objects remaining are either artifacts (which can never explain the immanent finality of natural objects) or abstract objects (which can never explain the concreteness of material things).

Nevertheless, I believe it is possible to construct metaphors for the way in which natural objects depend on their Creator. Thus I would consider any abstract object which is continually dependent on intelligent agents for its existence, to be a good metaphor for the way in which the world depends on God.

A hamburger recipe. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

What is needed, then, is a formal metaphor which is altogether free from the material limitations of an artifact (which lacks immanent finality), and which can therefore be legitimately applied to natural objects (in addition to artifacts), but which at the same time points clearly to an Intelligent Designer of natural objects – including (but not confined to) those objects which contain structures exhibiting specified complexity.

That formal metaphor, I would suggest, is that of a recipe, or sequence of instructions. Intelligent Design advocate Jay Richards invokes this metaphor in his book God and Evolution (Discover Institute Press, Seattle, 2010), in an essay entitled, "Understanding Intelligent design":

Imagine an expedition of future astronauts is exploring a distant planet. They find something that looks like a stack of thin tablets, which look like they contain written text. The language is unique; no one has seen it before; and the "book" is quite exotic. So it's given to a crack team of exoplanet cryptographers, who eventually determine that it is in fact a book – a cookbook. Now they know that the text was written by intelligent beings. (2010, p. 259)

Richards emphasizes that in this case, the design inference was made by setting aside the material features of the book – the tablets, binding and cover – and focusing on the text itself, which embodies the book's formal and final features. The metaphor, then, is that of a recipe itself.

Obviously, the natural world is not just a recipe. A recipe is an abstract object. It is purely formal, and contains no matter. The natural world, on the other hand, consists of concrete objects, each containing (prime) matter, which is realized under some (substantial) form.

Thus the recipe metaphor is not, and cannot be, a metaphor for any natural object. It can, however, serve as a metaphor for the way in which natural objects depend on their Maker, God.

Additionally, the natural world (i.e. the cosmos as a whole) can be legitimately said to embody a recipe. That's the whole point of the fine-funing argument. Finally, each and every living thing can be said to embody a recipe. That's the point conveyed by Dr. Don Johnson's excellent book, Programming of Life.

8.2.1 Is the recipe metaphor for life a scientifically legitimate one? Is it indispensable?

In this post, I will not be arguing that metaphors, such as that of the recipe, can be used to prove the existence of God, or even of a Designer. I shall address that issue in my next post. For the time being, I will simply note that in order for a metaphor to be legitimately used to establish the existence of a Designer or Creator, at least conditions need to be satisfied:

(i) the metaphor has to be a scientifically appropriate way of describing whatever it applies to;

(ii) the metaphor has to be a scientifically indispensable way of describing that which it applies to;

(iii) the metaphor has to contain descriptive terms which explicitly refer to mental acts (e.g. plans, promises); and

(iv) for the object to which the metaphor applies, there must be no feasible alternative pathway whereby the object could have come to instantiate the feature described by the metaphor.

I would propose that we can legitimately speak of recipes as occurring on two levels of the natural world: the cosmological and the biological.

8.2.2 Recipes in the fabric of the cosmos

A timeline of the Big Bang. Image courtesy of NASA and Wikipedia.

A physicist can look at the finely-tuned laws and fundamental constants of Nature, and grasp the fact that these laws, when combined with the initial conditions of the universe, can be regarded as a recipe for producing a cosmos which is capable of supporting life – including intelligent life. The recipe metaphor is particularly apt here, because even a slight variation in either the laws or the initial conditions would have disastrous consequences for the production of the desired result.

The natural kinds of objects which we find in the inorganic world are the product of the cosmic recipe that was used to create the universe – a recipe which took billions of years to produce its final results. Thus we can legitimately speak of these natural kinds as having been designed.

Natural objects in the inorganic world do not contain the recipe which produced them, but since we now know (thanks to the "fine-tuning" argument) there was a cosmic recipe, and since we know that the various natural kinds that occur in the world around us are essential to life, which (according to the fine-tuning argument) is what the cosmos was designed for, then we can be quite certain that the natural kinds that we find in the world were also designed.

8.2.3 Recipes in the biological world

|

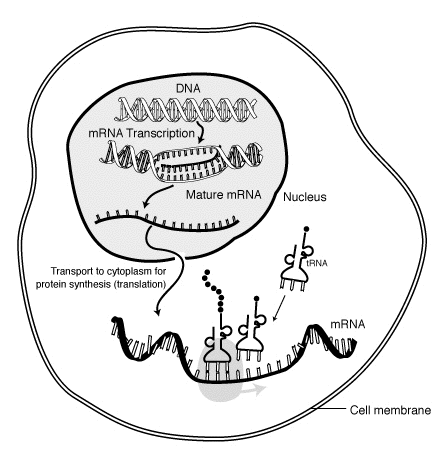

Left: RNA is transcribed in the nucleus; once completely processed, it is transported to the cytoplasm and translated by the ribosome (not shown). Image courtesy of National Institutes of Health, Sverdrup and Wikipedia.

Right: The elongation and membrane targeting stages of eukaryotic translation. The ribosome is green and yellow, the tRNAs are dark blue, and the other proteins involved are light blue. Image courtesy of Bensaccount and Wikipedia.

When it comes to living organisms, things are much more interesting. While the cosmic recipe established the conditions which were necessary for life to flourish, it does not follow that those natural conditions were sufficient to generate life. And indeed there is good reason to think that these conditions could not have done so.

Living things actually contain a kind of code, like that found in recipes. They are written in language, which contains instructions. What's special about a living thing, unlike a recipe book, is that the instructions it contains are decoded within the living thing itself. (This is an example of what Feser would call immanent causation.)

While a recipe can be used to make a product (e.g. a cake), it cannot be used to create another recipe. Living things are embodiments of recipes. Thus the recipes we find in living things can be said to reflect a second level of design, on top of the design we find in the cosmos at large.

It may help the reader if he/she tries to imagine a very "futuristic" book containing a list of recipes that (amazingly) are read and decoded within the book itself, that assembled the book together in the first place, that help keep the parts of the book together even when it is placed in a hostile environment (e.g. rainy weather), and that enable the book to make another copy of itself, embodying the same set of instructions. If a book could do all that, with all the parts (from the bottom level up) working systematically to preserve the integrity of the whole, then it would indeed be alive. However, I don't think that even Kindle will ever make a book like that!

If some of the terminology I used above to describe a living thing strikes some readers as rather extravagant, I can assure them that it is indeed scientifically legitimate. I have attached a list of reputable scientific sources at the end of this post, endorsing the use of the terms "code," "instructions," "recipe" and "program," to describe the workings of living organisms. But a picture is worth a thousand words, so in order to convey my point as clearly as possible, I would like to invite Professor Feser to watch a video produced by the Intelligent Design movement, just as I watched one of his videos. I'm referring to Dr. Don Johnson's "Programming of Life" video, which can be viewed here. The video is very professionally made, and watching it will indeed be a pleasure, for anyone who has not yet done so. The video should dispel any doubts as to the legitimacy of using informational terms to describe the workings of living organisms.

The next question we need to consider is whether the recipe metaphor is indispensable to biology, or whether it is just a useful way of picturing how living things work. I would argue that the sheer ubiquity of the informational terminology used by scientists to describe life, and the total absence of any atempts to explain life without resorting to such terminology, argues strongly for its indispensability to biology.

At any rate, the point I wish to make here is that the recipe metaphor is one which Professor Feser cannot reasonably take exception to, as it in no way reduces natural objects to the status of artifacts.

8.2.4 A short note regarding computers and living things

|

|

Left: A segment of a program, written in the Python programming language.

Right: A diagram illustrating the genetic code, according to the "central dogma", where DNA ic copied to RNA, which is used to make proteins. Shown here are the first few amino acids for the alpha subunit of hemoglobin. The sixth amino acid (glutamic acid, depicted by the symbol "E") is mutated in sickle cell anemia versions of the hemoglobin molecule.

Professor Feser would presumably object to the computer metaphor for the cell, which also features in the video. However, the definition of "computer" in the video is a very broad one, which focuses on its formal features rather than the relation between its material parts. In particular, the definition does not assume that the parts of a computer have been assembled together. It might help Professor Feser if he thinks of a virtual machine as a metaphor for the cell, rather than a physical computer. Thus on this broad definition, even a living thing could qualify as a computer, as long as it can generate meaningful output. As the "Programming of Life" video puts it:

The necessary and sufficient components of any functional computer are: memory for data storage; an executable program containing instructions for processing data; the processor which executes the instructions; and the capability to produce meaningful output...DNA and RNA can hold prescriptive information, or programs, and proteins can be used to hold, transfer or process data. Proteins are the output generated by the translation process of a ribosome's computer system.

I'd now like to return to the recipe metaphor, and explain how it can help us to understand both living things and the cosmos as a whole.

8.2.5 A question from Professor Feser: What do I mean by my talk of codes and programs?

In a post entitled, Scotism and ID (UPDATED) (April 27, 2010), Professor Feser makes the following astute comments on my use of the recipe metaphor for life:

...Torley's talk of a living thing's "program" or "code" is problematic. There seem to me to be three possible interpretations of such language. First, it could be meant as merely a metaphorical way of talking about what are nothing more than certain complex patterns of efficient causation. But in that case it is not clear that it can do the job Torley wants it to do, viz. to differentiate living things from non-living ones, since he evidently (and rightly) takes "finality" or teleology to be essential to understanding life. Second, it could instead be intended to describe irreducibly teleological features of living things that derive from an external source, i.e. a designer. But in that case any ID argument that proceeds from such a description of living things would be circular... Third, it could be taken as a way of describing certain immanently teleological features of organisms. But in that case Torley would be committed to an essentially Aristotelian non-mechanistic conception of life, and he has said that ID makes, for methodological purposes, no such commitment. (As I have argued elsewhere – e.g. here – "program" talk when used by scientists is best interpreted in this third, Aristotelian way.)

In response:

1. Living things are the only natural objects which embody a digital code. This codeit is not merely a complex pattern of efficient causation; it is irreducibly teleological. It contains instructions that will enable a growing living organism to build itself into a fully developed adult.

2. It would indeed be circular to assume at the outset that life embodies features which by definition require a Designer, and then to argue that such a Designer exists. But that's not what I'm doing. In my next post, I shall argue at length that rules make up the warp and woof of the natural world: they are found everywhere in things. Rules, however, are inherently linguistic, which means that the world can only be understood in explicitly mentalistic terms. On top of that, some natural objects (i.e. living things) embody a digital code, and contain a program directing their development into a mature adult. That doesn't prove they were designed. But unless there's a natural process that can generate programs without any foresight, then a Designer is the only logical explanation. I then argue that the data of science strongly point to the absence of such a magical process that can generate programs without any foresight. Ergo, there is a Designer.

3. I would agree with Feser's suggestion that talk of codes and programs should be taken as a way of describing certain immanently teleological features of organisms. However, there have been some defenders of Design arguments (e.g. Boyle) who eschewed immanent teleology, viewing it (wrongly, as I believe) as imputing too much to nature and not enough to God. People with this theological viewpoint, upon seeing the programs within the cell, would jump to the conclusion that God put them there, since they effectively view things as nothing more than artifacts. For my part, I think that the conclusion that these programs had an Intelligent Designer requires some argumentation, as well as empirical evidence, as I'll explain in my next post.

See http://lyfaber.blogspot.jp/2010/04/nature-artifacts-meaning-and-providence.html

8.2.6 How the recipe metaphor enhances the Intelligent Design argument

We can now see the beauty of the Intelligent Design argument, when it is formulated using the metaphor of a recipe: it successfully accounts for both the immanent finality of living things and their need for an Intelligent Cause. Because a living thing is able to read and decode its own instructions, its finality can only be described as immanent, and since the process of reading and decoding is unquestionably an internal one, it also exemplifies immanent causation. (When I say "read and decode," I do not mean to impute intelligence to living things; rather, what I mean to say is that living things follow certain set procedures which enable it to take the digital code in which their biological recipes are written, decipher this code, and then use that code to accomplish a specific task, which serves the built-in ends of the organism.) But the key point is that recipes have to be written in some sort of language - and language, by definition, is the kind of thing that only an intelligent being can produce. Books, after all, need authors. That is why life itself requires an Author.

The defects of Paley's watchmaker analogy are now readily apparent. Watches, unlike recipe books, don't contain a code, are not written in any kind of language and therefore contain no instructions. Thus their need for a Designer is not an inherent one: it is simply based on the fact that, it is extremely hard, in practice, for unguided processes to assemble a watch. And while the finality of a watch is extrinsic, insofar as the watch's time-telling function is imposed on the parts of the watch for the good of its future owner, this is certainly not true of the recipe book in my hypothetical example.

While we're on the subject of immanent finality, the recipe metaphor also illustrates why the argument for an Intelligent Cause is so much clearer for living things than for other natural objects in the world around us. Living things contain their own recipes, and recipes, by definition, require a recipe-writer. By contrast, most kinds of natural objects do not contain the recipes that were used to make them, as the cosmos unfolded over billions of years. Hence it is much easier to see why living things require an Author.

The opening bars of Mozart's Paris Symphony (No. 31). Because a symphony is not an artifact, and is continutally dependent on intelligent agents for its existence, I consider it to be a good metaphor for the way in which the world depends on God. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

However, there are two problems with the recipe metaphor for life. First, if the cosmos is pre-programmed to develop according to the recipe that defines it, and if life has evolved from the first living cell, which was produced according to a recipe, then how do we know that the Author of these recipes is still alive? Second, how do we know that there's just one Author of life and the cosmos? Why couldn't there be several?

To answer these questions, I'd like to go back to the lute metaphor employed by Professor William Dembski. One of the appealing features of this metaphor is that it emphasized the continual dependence of the cosmos on God. Can we, then, construct a formal metaphor which abstracts from the physical features of Dembski's lute, but preserves the ongoing relationship of dependence between the lute and the music-maker?

The obvious solution (and I know it's been proposed before) would be to liken the universe not to the lute itself, but to the melody played on the lute. A melody requires a musician who is making it – and unlike the recipe, the dependence is an ongoing one. But since the world contains a variety of natural objects, that all make different melodies, it would perhaps be more appropriate to liken it to a musical composition – say, a symphony – rather than a single melody. If the cosmos is like a musical composition which is continuously being played, then its Author must be alive and still making the "music of the spheres."

What is more, the musical metaphor helps us to see why there can only be one Author of Nature. A discordant musical composition might be the work of several musicians who are clashing with one another, but a harmonious composition points to unity. Likewise, the deep underlying unity of the laws of Nature points very clearly to the universe's having a single Author.

Another striking fact is that the laws of Nature are the same throughout the cosmos. Paley, writing in the nineteenth century, was also struck by the fact that "the laws of nature every where prevail; that they are uniform and universal" (1809, p. 446) – a fact which he adduced as evidence for the omnipresence of the Creator, before going on to argue for the unity of God:

Of the "Unity of the Deity," the proof is, the uniformity of plan observable in the universe. The universe itself is a system; each part either depending upon other parts, or being connected with other parts by some common law of motion, or by the presence of some common substance. (Paley, W. Natural Theology: or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, p. 449)

Interestingly, St. Thomas Aquinas' argument from the order and harmony of the cosmos, in his Summa Contra Gentiles Book I chapter 13, paragraph 35, reflects the same kind of reasoning:

Damascene proposes another argument for the same conclusion taken from the government of the world [De fide orthodoxa I, 3]. Averroes likewise hints at it [In II Physicorum]. The argument runs thus. Contrary and discordant things cannot, always or for the most part, be parts of one order except under someone's government, which enables all and each to tend to a definite end. But in the world we find that things of diverse natures come together under one order, and this not rarely or by chance, but always or for the most part. There must therefore be some being by whose providence the world is governed. This we call God.

It is nice to see that on this point, Aquinas and Paley completely agree.

Insofar as the different kinds of natural objects in the natural world tend to work together to make a harmonious whole, we can legitimately speak of Nature as a symphony. The metaphor is apt.

When we examine a living thing, however, the harmonious interplay of parts is still more evident, and our sense of wonder increases. If the universe can be aptly described as a symphony, which requires an Intelligent Player, how much more so a biological organism.

A winnowing machine. A hard-nosed skeptic would probably prefer to use this mechanical device as a metaphor to explain the cosmos and also the world of living things, rather than the recipe and symphony metaphors. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

So far, I have argued that the recipe and symphony metaphors are valid descriptions of the natural world as a whole, and also the biological world of the cell.But at this point, a hard-nosed skeptic might object as follows:

"I will concede that the universe - and to a much greater degree, the cell - gives the appearance of being designed - and if you wished to be poetic, you might even use the terms 'recipe' and 'symphony' to describe the order and harmony that we see in the cosmos, and also in the world of the cell. But appearances can be deceptive. You haven't addressed the question of whether the metaphors you invoke are the only way of understanding the cosmos, or life itself. What if I could show you a non-intentional metaphor that could explain the universe and also the world of living things? Here's one: a winnowing machine. I maintain that the universe we live in is just one of infinitely many. Most of these universes are "rejects" which are incapable of supporting life. Only a small proportion of universes are hospitable to life. Of course, our universe has to be a life-friendly one, because if it wasn't, we wouldn't be here! Similarly, our universe has to be one with regular, unfailing laws, because if it wasn't, we would have all died out long ago. The same goes for the origin and evolution of life. Even in life-friendly universes, life has failed to evolve on countless occasions, and on countless planets. We just happen to be living on a planet where the attempt succeeded - and after that, life took off. Once again, there's nothing mysterious about this: if it hadn't succeeded, we wouldn't be here. Time and space have done the winnowing. Given a big enough cosmos with a sufficiently large number of universes, the beauty and harmony we find in this one is an inevitability."

In my next post, I will be replying to the skeptic's objection. I shall argue that the very notion of a law of Nature points to a Creator, because it is a rule that needs to be expressed in language - and rules can only come from a Mind.

I'm going to anticipate a possible objection that Professor Feser might make at this point. He might argue as follows: "I'm willing to grant that your recipe and symphony metaphors are free from the defects of the watch metaphor for the cosmos. At least they don't turn the cosmos into a machine. But these new metaphors still fail to do justice to the cosmos, because they focus exclusively on the abstract formal (and final) features of the cosmos. Recipes and symphonies are essentially formal. They aren't physical things as such, although they may of course be written down on paper. The cosmos, however, contains matter as well as form, and without matter, you don't have a concrete natural object. What you have is, at best, a Platonic abstraction, rather than a real thing. For that reason, I would still regard your recipe and symphony and as an inadequate description of the real world. At best, they might establish the existence of a God Who could turn out to be a Maker of real things. The version of the Fifth Way which I defend in my book, Aquinas, does not require the use of such emaciated metaphors for the cosmos. Instead, it starts from a very simple and obvious fact: the fact that things have built-in tendencies, or dispositions, such as the tendency of ice to cool water. And it conclusively establishes that these things are directed to their ends by an Intelligence Who keeps them in being, and Whose nature is identical with His own Being – which entails that He must be an Infinite Being."

In response to the possible criticism that recipes and symphonies are purely formal, and hence an inadequate metaphor for physical objects, I should like to point out that I have absolutely no intention of using them as metaphors for objects. Rather, the point I wish to make, along with Professor Marie George, is simply that they are intrinsically dependent upon their Maker.

Professor Feser has said and written a lot about Aquinas' Fifth Way, and how it renders Intelligent Design arguments superfluous. In my next post, I'll argue that the reverse is actually the case: the Fifth Way fails unless it is buttressed by Intelligent Design arguments.

|

|

Top: A plant cell. Bottom: DNA transcription (simple transcription elongation). Images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Dr. Don Johnson, who has both a Ph.D. in chemistry and a Ph.D. in computer and information sciences. On April 8, 2010, Dr. Johnson gave a presentation entitled Bioinformatics: The Information in Life for the University of North Carolina Wilmington chapter of the Association for Computer Machinery. Dr. Johnson's presentation is now on-line here. Both the talk and accompanying handout notes can be accessed from Dr. Johnson's Web page. Dr. Johnson spent 20 years teaching in universities in Wisconsin, Minnesota, California, and Europe. Here's an excerpt from his presentation blurb:

Each cell of an organism has millions of interacting computers reading and processing digital information using algorithmic digital programs and digital codes to communicate and translate information.

I'd like to quote a brief excerpt from Dr. Johnson's presentation:

"Somehow we have a genetic operating system that is ubiquitous. All known life-forms have the same genetic code. They all have the same protein manufacturing facilities in the ribosomes. They all use the same types of techniques. So something is pre-existing, and the particular genome is the set of programs in the DNA for any particular organism. So the genome is not the DNA, and the DNA is not the program. The DNA is simply a storage device. The genome is the program that's stored in the storage device, and that depends on the particular organism we're talking about."

It is worth repeating Dr. Johnson's point that DNA itself is not a program. To describe it as one is an inaccurate oversimplification, which ignores the advances in cell biology that have taken place in the last few decades. Neither would it be accurate to say that the suite of programs running within the cell are simply written on its DNA. Instead, DNA could be better described as a data storage device, used by the programs running the cell.

What is important, however, is that we can legitimately speak of a network of regulatory programs existing within the cell, which DNA enables and of which DNA forms a vital part.

On a slide entitled "Information Systems In Life," Dr. Johnson points out that:

To sum up: the use of the word "program" to describe the workings of the cell is scientifically respectable. It is not just a figure of speech. It is literal.

But there's more. The following quotes, which are taken from impeccable scientific sources, establish the scientific legitimacy of using terms like "instructions," "code," "information" and "developmental program" when speaking of embryonic development (emphases are mine):

"We know that the instructions for how the egg develops into an adult are written in the linear sequence of bases along the DNA of the germ cells." James Watson et al., Molecular Biology of the Gene (4th Edition, 1987), p. 747.

And from a more recent source:

"The body plan of an animal, and hence its exact mode of development, is a property of its species and is thus encoded in the genome. Embryonic development is an enormous informational transaction, in which DNA sequence data generate and guide the system-wide spatial deployment of specific cellular functions." (Emerging properties of animal gene regulatory networks by Eric H. Davidson. Nature 468, issue 7326 [16 December 2010]: 911-920. doi:10.1038/nature09645. Davidson is a Professor of Cell Biology at the California Institute of Technology.)

Here's another recent quote, from an article by Schnorrer et al., on the development of muscle function in the fruitfly Drosophila:

"It is fascinating how the genetic programme of an organism is able to produce such different cell types out of identical precursor cells." (Schnorrer F., C. Schonbauer, C. Langer, G. Dietzl, M. Novatchkova, K. Schernhuber, M. Fellner, A. Azaryan, M. Radolf, A. Stark, K. Keleman, & B. Dickson, Systematic Genetic Analysis of Muscle Morphogenesis and Function in Drosophila. Nature, 464, 287-291 (11 March 2010). doi:10.1038/nature08799.)

And here is a quote from Professor Richard Dawkins, in The Greatest Show on Earth (Transworld Publishers, London, Black Swan edition, 2010, p. 217):

"...[T]here is a mystery, verging on the miraculous (but never quite getting there) in the very fact that a single cell gives rise to a body in all its complexity. And the mystery is only somewhat mitigated by the feat's being achieved with the aid of DNA instructions. The reason the mystery remains is that we find it hard to imagine, even in principle, how we might set about writing the instructions for building a body in the way the body is in fact built, namely by what I have just called 'self-assembly', which is related to what computer programmers call a 'bottom-up', as opposed to a 'top-down', procedure.

Dawkins goes on to say that in his view, "local rules" make it plausible that this process was accomplished naturally, over a period of one billion years. But what I find interesting is that he nevertheless feels the need to employ terms like "instructions" and "rules," in order to describe the process whereby an embryo is put together.