|

|

|

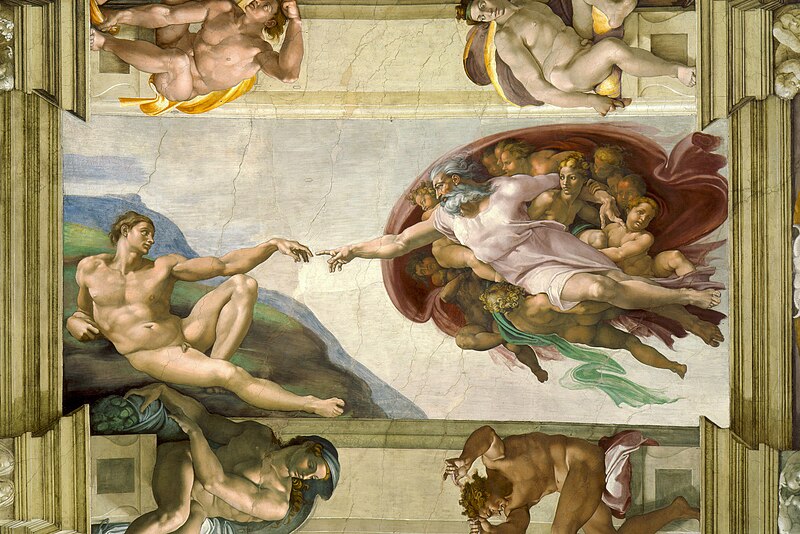

Left: The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo. Sistine Chapel ceiling, circa 1511. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

According to Professor Feser, creation is entirely a top-down process. God can make a man from dust simply by saying, "Dust, become a man." In so doing, He does not - indeed, could not - achieve His result by tinkering with the dust particles.

I maintain, on the contrary, that in the process of making a man from dust, God would have to rearrange the dust particles from the bottom up, while simultaneously bestowing the substantial form of a man on the underlying (prime) matter. Simply telling dust to become a man fails to specify what kind of man God wants - e.g. how tall he should be, what blood type he should have, what kind of face he should have, and so on. It also fails to specify the micro-level properties of the man in question - e.g. how many cells his body should have, and exactly what sequence of bases he should have in his DNA.

Middle: A hotel suite. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. David Bowman is transported through space to what looks like a hotel suite. Bowman soon realizes, however, that the suite is a facade, constructed to make him feel at ease. He discovers this when he finds that the "things" in the suite only bear a superficial resemblance to the real-life objects that they were designed to replicate. For instance, the books in the suite have recognizable titles, but are empty inside. There's a refrigerator and familiar looking boxes of food. Inside the boxes, though, there is only a blue goo that resembles a pudding. In short: it is the lack of specificity of the items in the suite, at the finer level of detail, that makes Dr. Bowman realize that they are not real objects but replicas. The point I wish to make in this section is to argue that in order for something to be a real natural object, it has to be fully specified, all the way down to the bottom level. Where I part company with Professor Feser is that he seems to believe that God can dodge the "specificity problem": when He makes something, He doesn't have to specify its details, all the way down. I maintain that He does.

Right: Wernher von Braun's 1952 concept of a space station, which served as a model for the space station in Arthur C. Clarke's novel, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In this section, I shall attempt to argue that in order for a thing to be a genuine entity in its own right (and not just a virtual reality imitation of an entity), it has to be fully specified, at all levels, from the bottom to the top. I will argue that Professor Feser's account of "thinghood" is severely defective on this point: he apparently thinks that things can be automatically built by God, from the top down, without the need for God to precisely specify their lower-level properties. The same deficiency appears in Feser's account of human action: Feser apparently thinks that the goal of a human action is sufficient to specify the exact sequence of bodily movements made by a person in performing that action. Thus I would contend that it is Feser, and not Intelligent Design proponents, who robs things of their "thinghood", with his top-down approach to design.

How Professor Feser thinks God makes things

In a post entitled, ID theory, Aquinas, and the origin of life: A reply to Torley (April 16, 2010), Professor Feser spelt out exactly what he believes happens when God creates something:

...[W]hether or not we think of God as specially creating life in an extraordinary intervention in the natural order, the way He creates is not properly understood on the model of human artifice. He does not make a living thing the way a watchmaker makes a watch or the way a builder builds a house. He does not take pre-existing raw materials and put them into some new configuration; nor does He even create the raw materials while simultaneously putting the configuration into them. (As I’ve said before, temporal considerations are not to the point.) Rather (as I put it in my earlier post) he creates by conjoining an essence to an act of existence, where the essence in question is a composite of substantial form and prime matter. That is the only way something that is “natural” rather than "artificial" in Aristotle’s technical senses of those terms possibly could be created.

In a comment on another post, entitled, Nature versus Art (April 30, 2011), Professor Feser also asserted that God could, if He wished, make a man from the dust of the ground, simply by saying, "Dust, become a man." As he wrote back to me, when I asked him about the sequence of steps involved in such a transformation:

Forming a man from the dust of the ground involves causing the prime matter which had the substantial form of dust to take on instead the substantial form of a man. I'm not sure what "sequence of steps" you have in mind. There's no sequence involved (nor any super-engineering -- God is above such trivia). It's just God "saying," as it were: "Dust, become a man." And boom, you've got your man.(For the New Atheist types out there, no, this isn't "magic." Rather, it's something perfectly rationally intelligible in itself and at least partially intelligible to our finite minds once we do some metaphysics. It's just something that only that in which essence and existence are identical, that which is pure actuality, etc. is capable of, and we aren't. We have to work through other pre-existing material substances and thus have to do engineering and the like in order to make things. God, who is immaterial, the source of all causal power, etc. doesn't need to do that and indeed cannot intelligibly be said to do it.)

Professor Feser is not alone in envisaging God's creative acts in this manner. Thomist scholar Christopher Martin is of the same view. Feser quotes a long passage from Martin in his post, Thomism versus the Design argument (2010), from which I shall reproduce the following excerpt:

The Being whose existence is revealed to us by the argument from design is not God but the Great Architect of the Deists and Freemasons, an impostor disguised as God, a stern, kindly, and immensely clever old English gentleman, equipped with apron, trowel, square and compasses...The Great Architect is not God because he is just someone like us but a lot older, cleverer and more skilful. He decides what he wants to do and therefore sets about doing the things he needs to do to achieve it. God is not like that... [T]here is nothing that God is up to, nothing he needs to get done, nothing he needs to do to get things done... Acorns for the sake of oak trees, to repeat an example of Geach's, are definitely something that God wants, since that is the way things are. But it is not that God has any special desire for oak trees (as the Great Architect might), and for that reason finds himself obliged to fiddle about with acorns. If God wants oak-trees, he can have them, zap! You want oak trees, you got 'em. "Let there be oak trees", by inference, is one of the things said on the third day of creation, and oak trees are made. There is no suggestion that acorns have to come first: indeed, the suggestion is quite the other way around. To "which came first, the acorn or the oak?" it looks as if the answer is quite definitely "the oak". In any case, what's so special about oak trees that God should have to fiddle around with acorns to make them? God is mysterious: the whole objection to the great architect is that we know him all too well, since he is one of us. Whatever God is, God is not one of us: a sobering thought for those who use "one of us" as their highest term of approbation.

Christopher Martin's slighting references to the Great Architect display his lack of familiarity with history. I have already shown, in section 4.7. above, that the reference to God as the "Great Architect" goes back not to the 18th century Freemasons but to John Calvin in the 16th century, and that artistic depictions of God as an Architect go back to the Middle Ages.

If Martin believes that proponents of the Design Argument think God needs to make acorns in order to make oaks, then I can only say that he doesn't know much about the Intelligent Design movement. I don't know of any Intelligent Design proponent who holds such a view. However, what I would maintain, as an ID advocate, is that if God wishes to make an oak, He needs to specify, down to the last detail, the genetic information He wishes that oak to contain in its cells. If He didn't do that, then the thing He made wouldn't be an oak at all. Indeed, it wouldn't be alive at all. It wouldn't even be an entity, but only a virtual imitation at best.

Similarly, I maintain that Feser is completely wrong in his account of how God could make a man from dust. I hold that no-one, not even God, can make a man from dust without specifying, at the atomic level, what should go where (and, I might add, doing quite a lot of nuclear transmutation as well). The reason has nothing to do with any limitations on God's power; rather, it has to do with the very nature of things. In a nutshell: the top-level of an entity does not, and cannot, determine all of the details at the bottom. If God tried to make men from the top down, without specifying their constituent atomic particles, then they wouldn't be men at all. They'd be no more real than the things in the movie, "The Matrix." Real entities – be they people, animals, plants or minerals – have to be fully specified at the bottom level as well as the top. Otherwise, they're not entities at all.

|

|

|

Left: Daniel Radcliffe, the actor who played the part of Harry Potter in the Harry Potter movie series. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Middle: The floor plan of a typical house. Image courtesy of Wikipedia. Nobody knows exactly what the floor plan of Harry Potter's house looks like, although that has not stopped some fans from making very ingenious guesses (see here and here). That's because Harry Potter's house, being a fictional object, has not been completely specified at all levels of description by its author, J.K.Rowling.

Right: J. K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter series.

To illustrate why real entities have to be fully specified at the bottom level as well as the top, consider the fictional character, Harry Potter. In the story, Harry Potter lives at Number Four, Privet Drive, the home of his Aunt Petunia, Uncle Vernon, and their son Dudley. Now ask yourself this: what color is the roof of Harry Potter's house? Of course, you don't know. That's because the book's author, Joanne Kathleen Rowling, didn't tell you. And although she is famous for writing detailed back stories for her books, I doubt whether even she has ever asked herself this simple question. In the story, the color of the roof remains unspecified, and the reader is free to imagine it to be any color that he or she pleases.

That's fine in a work of fiction, but real roofs have to have a specific color. No roof in the real world has ever had an undetermined color. Even if it was never painted, it always had a color of some sort – namely, the natural color of the roofing material. Real entities need to be specified at the bottom level; otherwise they are not real at all.

Let us suppose, now, that God commanded a piece of dust to become a man, as Professor Feser supposes he did. On behalf of the dust, I would like to reply: "What kind of man would you like me to become, Lord? A tall one or a short one? Brown eyes or blue? A Will Smith lookalike or a Tom Cruise replica? Blood type A, B, AB or O? Oh, and what about the micro-level properties of the man you want me to be? Exactly how many cells should this individual have? What sequence of bases should he have in his DNA? I'm afraid I can do nothing, Lord, unless you tell me exactly what you want." I won't belabor the point here: the difficulty should be obvious. The problem with merely telling the dust to become a man is that it under-specifies the effect – or in philosophical jargon, under-determines it. And since dust is unable to make a choice between alternatives – even a random one – then nothing at all will get done, if God commands dust to simply become a man. To get a real man, every single detail in the man’s anatomy has to be specified, right down to the atomic level.

Now we can see why the psalmist wrote: "For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother's womb" (Psalm 139:13).

So contrary to what Feser wrote, I would maintain that God does have to do super-engineering, if He designs an organism. This point has obvious religious implications: for instance, if you happen to believe in the virginal conception of Jesus (as I do) then you will have to grapple with what biologist and Intelligent Design proponent Stephen Jones calls "the mechanics of the Incarnation" (see here for a very interesting blog by Jones on this topic). There's just no getting around the mechanics of design, even if you're a Deity. The reason is simple: in the real world, things are specified at all levels, including the bottom level.

Thus my answer to Descartes' skeptical question, "How can I know whether the world around me is real?" would be: "Try taking it apart. Look at the next layer down, and the layer below that. If you come across a layer whose properties are unspecified, then your world is a fake one." (Someone will probably ask me about quantum indeterminacy at this point. Here's my answer: at least there's determinacy when we make a measurement, so that's OK. What would be troubling would be making a measurement and getting no result.)

A clarification: Intelligent Design does not claim that information is added to things extraneously; rather, it constitutes things

A yellow-bellied sea-snake. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Professor Feser argues, correctly, that the biological information that characterizes a snake is inseparable from its substantial form - i.e. that by virtue of which it is a snake, and not some other kind of animal. Feser might be pleasantly surprised to learn that many Intelligent Design proponents would entirely agree with him on this point.

In a recent blog post entitled, Reply to Torley and Cudworth, Feser criticizes the notion, which he imputes to Intelligent Design proponents, that information can be "poured into" pre-existing things:

A natural object is not a collection of otherwise meaningless or information-free parts to which information, function, teleology or final cause has to be "imparted," and making a natural object is not a kind of two-stage process which consists first of creating an otherwise meaningless but free-standing material structure and then "introducing" some information or functional properties into it. In the case of a snake or a strand of DNA, for example, there is for A-T simply no such thing as a natural substance which somehow has all the material and behavioral properties of a snake or a strand of DNA and yet still lacks the "information content" or teleological features typical of snakes or DNA. And so, when God makes a snake or a strand of DNA, He doesn't first make an otherwise "information-free" or teleology-free material structure and then "impart" some information or final causality to it, as if carrying out the second stage in a two-stage process. Such a way of thinking of "design" is possible only against the background of a modern conception of matter which has extruded from it the notions of substantial form and immanent teleology. In short, it is possible only given a rejection of the Aristotelian conception of nature. For on an Aristotelian conception, to be a natural substance at all in the first place is necessarily to have a substantial form and immanent teleology – and therefore, necessarily, already to embody "information."

Professor Feser will be delighted to learn that I, like other Intelligent Design proponents, completely agree with him on this point. We agree that the biological information that characterizes a living thing is not accidental to it; rather, it is part of its very essence.

Thus I would agree with Feser that if God were to make a man from dust, it would have to be via a single-stage process. It would be absurd to claim that something might have all the material properties of a man (or a snake, to use Feser's illustration), and yet still not be a man (or a snake). Feser is perfectly correct in saying that for something to have the substantial form of a man (or a snake), it must already embody the "information" that characterizes it as such.

Where I differ from Feser is that he appears to believe that the biological information in Adam's body - on both the micro-level and the macro-level - is an automatic consequence of his having a human form. God says, "Dust, become a man", and that's it. Adam has the body he needs. I maintain, on the contrary, that while Adam's having a human substantial form (or soul) certainly entails that he will have the requisite biological information in his body, it does not specify which biological information he has. Human beings, after all, come in all shapes and sizes. To make Adam have this biological information in his body, God needs to specify the sequence of Adam's genome (among other things), at the same time as he commands dust to acquire a human form.

Rene Descartes' illustration of dualism, in "Meditations metaphysiques", explaining the function of the pineal gland. Inputs are passed on by the sensory organs to the pineal gland in the brain and from there to the immaterial spirit. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The same "top-down" thinking that led Feser astray with his approach to design also ruins his solution to the famous interaction problem addressed by Descartes in the 17th century: how can the mind and body interact? In a post entitled, The interaction problem, Feser asserts that the interaction problem only arises if you think (as Descartes is supposed to have done) that mind and body are two things, and that the former interacts with the latter in a purely mechanical fashion.

Professor Feser argues that the interaction problem disappears when we treat the soul as the substantial form of the body (as Aristotle did) and not as a separate thing (as Descartes is said to have done). That is, my soul is what makes my body a human body, and not the body of a chimp, or some other organism, or a pile of dust. Feser contends that whenever I act, my actions have a final cause (the end I'm trying to achieve), a formal cause (the pattern or structure of the action itself), a material cause (the matter in my body that actually carries out the action) and an efficient cause (whatever it is that makes my body move when I act).

Thus Feser maintains that when I perform a bodily action such as writing a blog, the movement of neurons in my brain and arm and the attendant flexing of muscles constitute the material cause of my action, and also the efficient cause, presumably because these neurons are the parts of my body whose movements cause my hands to move when I press the keys on my computer. My thoughts and intentions, on the other hand, comprise the formal cause and the final cause of my action: my thoughts give the blog post the "form" or structure that it has as an essay, while my intentions define my purpose for writing the post. In Feser's words:

As I move my fingers across the keyboard, then, what is occurring is not the transfer of energy (or whatever) from some Cartesian immaterial substance to a material one (my brain), which sets up a series of neural events that are from that point on "on their own" as it were, with no further action required of the soul. There is just one substance, namely me, though a substance the understanding of which requires taking note of each of its formal-, material-, final- and efficient-causal aspects. To be sure, my action counts as writing a blog post rather than (say) undergoing a muscular spasm in part because of the specific pattern of neural events, muscular contractions, and so forth underlying it. But only in part. Yet that does not mean that there is an entirely separate set of events occurring in a separate substance that somehow influences, from outside as it were, the goings on in the body. Rather, the neuromuscular processes are by themselves only the material-cum-efficient causal aspect of a single event of which my thoughts and intentions are the formal-cum-final causal aspect. (Bold print mine, italics Feser's - VJT.)

(The interaction problem, October 8, 2008.)

Thus Feser rejects the Cartesian view that there is "an entirely separate set of events occurring in a separate substance that somehow influences, from outside as it were, the goings on in the body," on the grounds that "[t]he soul doesn't 'interact' with the body considered as an independently existing object." The soul, on Feser's view, is not the efficient cause of the body's movements, but its formal cause: it is what unites the matter of the body and makes it a human body in the first place. As he puts it:

The soul doesn't "interact" with the body considered as an independently existing object, but rather constitutes the matter of the human body as a human body in the first place, as its formal (as opposed to efficient) cause.

(The interaction problem, October 8, 2008.)

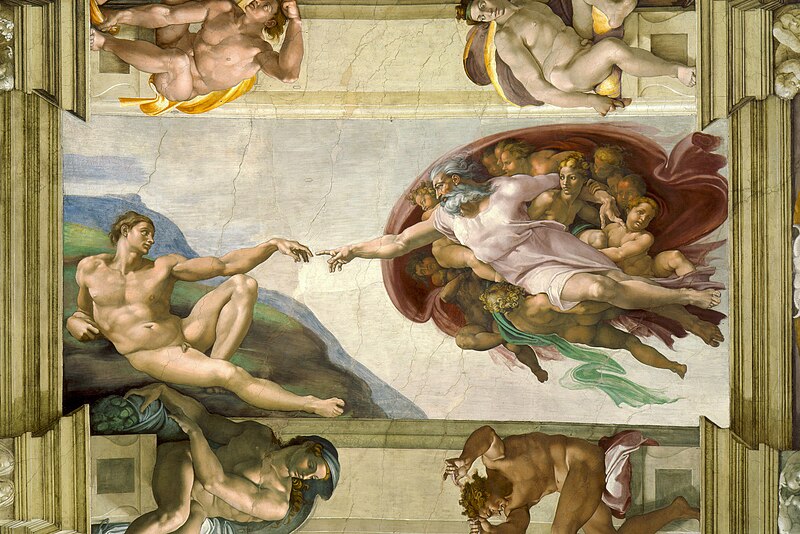

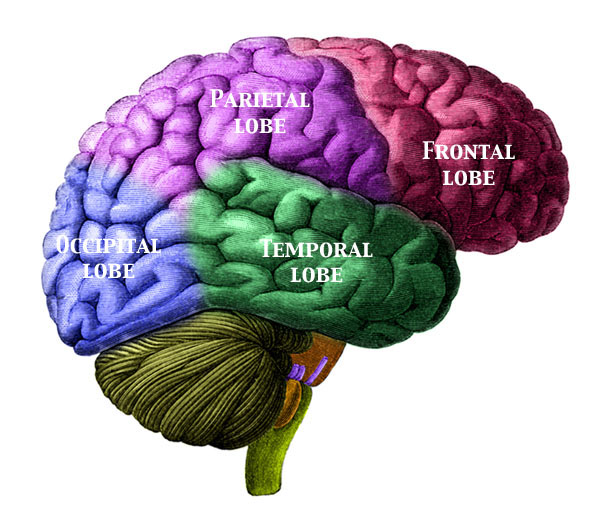

The human brain, showing the various lobes. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

For Professor Feser, the soul is the body's formal cause, which unites the matter of the body and makes it a human body. However, Feser rejects the notion that the soul is the efficient cause of the body's movements. Thus for Feser, the interaction problem (how does the soul interact with the brain?) simply does not arise. However, I reject this view, as it fails to explain what makes my hand move in exactly this way, when I decide to move it. Feser's account of bodily action is thus under-specified. (If Feser were a physical determinist, he could say that the environmental stimuli affecting me determine the way in which my hand moves; however, Feser is not a physical determinist.)

I maintain, on the contrary, that persons, at a holistic level, are capable of performing non-bodily acts (e.g. decisions to move) which affect their brains. A person is thus the efficient cause of the movement of certain neurons in the brain which then initiates a bodily action (such as raising your hand, or writing a blog). Thus on my account, the interaction problem is real: how does the soul interact with neurons in the brain, when we decide to perform bodily movements? The short answer is that God made us with this built-in ability.

Feser is surely right when he asserts that the soul doesn't interact with the body as an independently existing object. But this is a very extreme form of dualism, and it is doubtful whether Descartes himself held to such a view. One can affirm that soul and body belong to the same substance, and yet contend that they interact. Indeed, it can be argued that this was Aquinas' view. Consider the following passage, in which Aquinas addresses the question of whether the will is moved by a heavenly body:

[S]ome have maintained that heavenly bodies have an influence on the human will, in the same way as some exterior agent moves the will, as to the exercise of its act. But this is impossible. For the "will," as stated in De Anima iii, 9, "is in the reason." Now the reason is a power of the soul, not bound to a bodily organ: wherefore it follows that the will is a power absolutely incorporeal and immaterial. But it is evident that no body can act on what is incorporeal, but rather the reverse: because things incorporeal and immaterial have a power more formal and more universal than any corporeal things whatever. Therefore it is impossible for a heavenly body to act directly on the intellect or will. (Summa Theologica I-II, q. 9, art. 5)

Aquinas seems to be saying here that while no body can act upon the will, the will (being incorporeal) can act upon a body.

Aquinas is even more explicit in Summa Theologica I, q. 82, art. 4 (Does the will move the intellect?), where he writes that "the will as agent moves all the powers of the soul to their respective acts, except the natural powers of the vegetative part, which are not subject to our will." Here, Aquinas seems to be saying that the will is the efficient cause of all our voluntary movements, but not of our vegetative functions, such as digestion and breathing. This is borne out by Summa Theologica I, q. 76, art. 6 (Is the intellectual soul united to such a body by means of another body?), where Aquinas declares that the intellectual soul "guides and moves the body by its power and virtue" (reply to objection 3).

An alternative dualist position, which I espouse, is that persons are capable of interacting with their bodies - and in particular, with their brains, thereby causing their bodies to move. This person-body dualism is perfectly compatible with a recognition that the soul is the form of the body, as Aristotle declared it to be.

Regardless of what view one holds with regard to interactionist dualism, the key problem with Feser's "solution" to the interaction problem is that it dodges the critical question of what causes the neurons in my brain to move in the first place, when I am writing a blog. Consider the following example. I am writing an article for a blog, and I get stuck in my train of thought. For a while, I stare into space, resting my chin on my hands, and cogitating about what to write next. Suddenly, a bright idea comes to me, and I reach out to the keyboard and write an "inspired" sentence that perfectly expresses what I wanted to say.

Feser would have us believe that the final cause – the goal of writing that "inspired" sentence – is the ultimate explanation of why I moved my arms, hands and fingers in the way I did when I typed it. This invites the further question: did the goal of writing that sentence make the neurons in my brain move, subsequently leading to the sequence of arm, hand and finger movements which occurred when I typed the sentence? Yes or no? Either answer is fatal to Feser's "solution" of the interaction problem.

If Feser's answer is "Yes," then he is faced with a problem of under-determination. The goal of writing the "inspired" sentence doesn't specify exactly how I will move my arms, hands and fingers when I type it. There are countless ways in which I could type the sentence, after all. Even the spatial trajectory taken by my arm and hand when I reach out to type the first letter of the sentence is merely one of numberless possible trajectories that could have been taken. What, then, does determine the way in which my arms, hands and fingers move, when I type? Obviously the goal alone is not enough.

We can see here that the same problem of under-determination arises here as in Feser's account of how God makes a man from dust. According to Feser, God simply tells the dust to become a man, and that’s enough. The problem, as I pointed out above, is that this generalDivine command doesn't specify the dimensions, weight or molecular composition of the man God wishes to create – which is why I maintained that even God has to design a man from the bottom up, when and if He chooses to make one from dust.

So Feser, it seems, will have to answer "No" to the question of whether the goal of writing my "inspired" sentence makes the neurons in my brain move, when I write it. He might want to add that goals, as such, don't make things move in any case: that’s what efficient causes do, and a goal is a final cause. Fine; but then I would ask him: what does determine the movements of neurons in my brain, when I type? If outside stimuli impinging on my body cause the neurons in my brain to move, then it seems there is no room for human freedom, as the action of these stimuli can be described in a deterministic fashion on a molecular level. Throwing in a bit of indeterminism at the subatomic level doesn’t seem to help matters, either; it just creates an element of randomness, which is not the same thing as freedom.

Students raising their right hand while pledging to the American flag with the Bellamy salute in 1941. The salute was used for the Pledge of Allegiance in the United States from 1892 to 1942, when it was officially replaced by the hand-over-the-heart gesture. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The simple act of raising one's right hand invites the philosophical question: if I interact with my brain (as many dualists assert), then how exactly does my mental decision to raise my arm affect my brain, causing my arm to go up? The short, simple answer is that God designed me in such a way that whenever I decide to move my right arm, the area in my brain which governs right arm movements is activated.

It seems to me, then, that in order to restore human freedom, we have to affirm that people (notice that I say "people", not Cartesian souls) can influence their brains. In other words, a person's choices can determine events at a microscopic level, such as their neuro-muscular movements. There's no need to invoke Descartes' ghostly mind-body interactionism, but there's no getting away from person-brain interactionism. Contrary to Feser, I assert that people, by virtue of their immaterial thoughts and decisions, can and do interact with their brains. If they didn't, nothing would ever get done.

But how, it might be asked, can I possibly influence my brain simply by deciding to raise my right arm, especially if I am not thinking about my brain as such, or if (like a very young child) I don't even know that I have a brain?

The short answer, I believe, is: that's just the way God made us. God has designed the human body in such a way that whenever I perform the immaterial mental act of deciding to move my right arm, region "X" of the motor homunculus in my brain (i.e. the area in my brain which governs right arm movements) is activated, and whenever I decide to move my right leg instead, region "Y" of the motor homunculus in my brain (which governs right leg movements) is activated. That in turn means that the matter in my brain must have been designed by God – acting in a bottom-up fashion, of course – with the odd but felicitous built-in property of being responsive to my will. I realize that the foregoing account of the mechanics of voluntary movement is a grossly oversimplified one; a more detailed account would incorporate such features as feedback, forward modeling, fine motor-tuning and proprioception – as well as the fact that many of our movements are performed unconsciously: a good typist (which I'm not) might reach out to hit a key on the keyboard of his/her computer without even thinking about that fact.

The point I wanted to make, however, is just as that there's no escaping the nitty-gritty of the bottom level when we consider the question of how God acts, so too, there’s no escaping the nitty-gritty of the bottom level when we consider the question of how we act. The human brain has to have built-in features (designed by God) allowing it to respond to our immaterial choices, and humans have to have the built-in capacity to interact with the appropriate neurons in their brains when they decide to perform some bodily movement – even if they have no idea how this interaction occurs. There's no getting away from the bottom level. To suppose otherwise, as Professor Feser does, is to overlook the stubborn, solid "thinginess" of things.

I've said enough about Feser's "magical" top-down view of things fails to do justice to their "thinghood." Let us now return to Feser's discussion of Paley's watch metaphor. As we'll see, the metaphor is a lot older than Paley. It goes back to Roman times.

In an article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entitled, Divine Providence, Hugh McCann considers various proposed solutions to the question of how God's foreknowledge can be reconciled with human free will, and finds them all wanting. In McCann's view, the only satisfactory solution to the question is that God knows our choices by controlling them. Nevertheless, he thinks that God's controlling our choices is still perfectly compatible with our possessing libertarian free will:

If the views considered thus far all fail, theists have no choice but to place the decisions and willings of rational creatures under God's creative authority. Only by so doing is it possible to restore to him complete control over the course of events in the world, and only in this way can he know as creator what world he is creating, and so be omniscient. If all of our decisions and actions occur by God's creative decree, then all possible worlds are made feasible for him. He can create as he wishes, with full assurance as to the outcome. And he can know how things will go, in particular how we will decide and act, simply by knowing his own intentions as to what our decisions and actions will be...A useful analogy that may be drawn here is to the relationship between the author of a story, and the characters within it. The author does not enter into the story herself, nor does she act upon the characters in such a way as to force them to do the things they do. Rather, she creates them in their doings, so that they are able to behave freely in the world of the novel. On the traditional account, God's relation to his creatures is similar. As creator, he is the "first cause" of us and of our actions, but his causality works in such a way that we are not acted upon, and so are able to exercise our wills freely in deciding and acting. If this is correct, then as Augustine and Aquinas both insist, God's creative activity does not violate libertarian freedom, for it does not count as an independent determining condition of creaturely decision and action.

Interestingly, Professor Feser thinks that McCann's analogy is correct, insofar as it relates to human freedom. In a post entitled, Are you for real? (May 8, 2011), he comments on McCann's analogy, which I had earlier alerted him to:

Now it seems to me from the passage Torley cites that McCann himself does not take the view that we are really just fictional characters; he appeals to the notion only as an analogy useful for helping us to understand why divine causality is not incompatible with human freedom. The idea is that God's causality is not like that of one character, object, or event in a story among others; it is more like that of the author of the story. Hence to say that God is the ultimate source of all causality is not like saying that He is comparable to a hypnotist in a story who brainwashes people to do his bidding, or a mad scientist who controls them via some electronic device implanted in their brains. He is more like the writer who decides that the characters will interact in such-and-such a way. And so His being the ultimate source of all causality is no more incompatible with human freedom than the fact that an author decides that, as part of a mystery story, a character will freely choose to commit a murder, is incompatible with the claim that the character in question really committed the murder freely.

While I think that there are certain attractive features in McCann's analogy between God and the author of a book - it explains creation ex nihilo very straightforwardly, for instance - I think McCann's modern defense of universal predestination fails utterly as an account of human freedom, for two reasons.

The first reason is that if McCann's "author" analogy for Divine causality of our choices is true, then it would be utterly inconsistent of God, as the author of our actions, to praise us for our good choices, or find fault with us for our bad ones. And yet, as Christians, we believe that God does just that. (For instance, in Matthew 25: 31-46, the parable of the last judgement, God finds fault with the goats for not helping the needy.) An author may like or dislike one of his or her characters, but an author cannot logically find fault with one of his or her characters and say to that character, "You should not have done that." Why not? Because the author made the character act in that way, since the author wrote the story that way.

The second problem with McCann's model is that if God decides to damn some people, then His decision to create them in the first place is morally indefensible. It is all very well to say that although their actions are ordained by God, they nevertheless go to Hell freely. The problem is that on this account, it is God who creates the people that go to Hell; moreover, God is the author of the decisions that send these people to Hell; thus God does everything that is needed to ensure their damnation.

I regard these unpalatable consequences of McCann's model of Divine foreknowledge as tantamount to a theological reductio ad absurdum. I therefore find it alarming that Professor Feser defends McCann's model of Divine predestination. Evidently, Feser also believes that God knows our choices by controlling them.

I should add that if McCann and Feser are right in saying that God knows our choices in the way that the author of a book knows what his/her characters are doing, then that would entail that God is the Ultimate Author of all of the following:

Is Professor Feser really willing to bite the bullet and say that God is the Ultimate Author of all these things?

As I have said, I do not believe that God knows our choices by controlling them. My own view (following Boethius) is that God knows our choices by (timelessly) interacting with us: He is thus made aware of our choices. Boethius' metaphor of the high tower is apposite here: God timelessly observes all past, present and future events. Such a view maintains libertarian freedom, leaves us genuinely accountable for our choices, and makes humans (not God) the ultimate authors of evil and stupid thoughts, words and deeds.

Theologians sometimes speak of God as having scientia visionis, or knowledge of vision, by which He knows all real things in the past, the present and the future, and foresees the free acts of the rational creatures with infallible certainty. On the account I am defending here, the term "vision" is an apt one, since God is timelessly made aware of our choices, and knows them as a result of our making them.

Professor Feser, as a Thomist, would deny that God can be made aware of anything, as that would make Him (a) passive and (b) dependent on His creatures for His knowledge of their choices. In response, I would argue that (a) the fact that God is purely active in His essence does not make Him purely active in His knowledge of contingent events, and (b) the fact that creatures are totally dependent on God for their existence does not preclude God from being dependent on them for His knowledge of their contingent choices.

I'd now like to address the fundamental question: what does it mean for something to be real?

I would suggest that an entity is real if and only if:

(i) its properties are fully specified - or more accurately, a measurement of any property (or attribute) of that entity always yields a specific value, at any given moment of its existence;

(ii) its relationships are fully specified - or more accurately, a measurement of its relationship to any other given entity always yields a specific value, at any given moment of its existence;

(iii) it is individualized - i.e. it is distinguishable as an individual from other entities of the same kind, during at least some moments of its existence;

(iv) it is concrete, in the sense that measurements of its location in space and/or time yield definite values.

Note on conditions (i) and (ii):

By "fully specified", I do not necessarily mean "specified by God". (Entities with libertarian free will are to some degree self-specifying.) By "fully specified", I simply mean that a measurement of any attribute of that entity always yields a definite value. It may not be possible to measure all of the entity's properties at the same time, however. (For instance, the Uncertainty Principle tells us that we cannot measure an electron's position and momentum simultaneously.)

Note on condition (iii):

Two entities may be indistinguishable from each other at some points in time (e.g. two bosons, which can both be present at the same place at the same time). However, I would argue that it makes no sense to speak of two entities which are indistinguishable from each other at all points in time.

Note on condition (iv):

When an entity's location in space and time is not being measured, it need not have a definite value.

I have argued above that entities as defined by Professor Feser are under-specified, and hence fail to meet conditions (i) and (ii): according to Feser, God can make a man simply by commanding some dust to become a man, without specifying the man's properties or relationships to other entities.

Another disagreement between Professor Feser and myself is that even if Feser were to accept conditions (i) to (iv), he would definitely want to add a fifth condition to the list above:

(v) the entity's essence has been endowed with existence.

I think the fifth condition is redundant.

The concept of a phoenix is often cited as an example of something which is not real. However, as it fails all four criteria, I think it is a rather poor example. Someone might ask: "What if God were to mentally envisage a particular phoenix, and completely specify its properties in His mind? Would that make it real?" I would say no, as its relationship with other entities would not be fully specified. But what if these relationships were fully specified in the mind of God? In other words, what if God were to make up a story of that phoenix's complete life history, and fill in the story with other individuals that were specified to the same level of detail? What if, in addition to that, the entities were clearly distinguishable from each other, and had definite locations in space and time, in the story envisaged by God? Then I would say: that would be enough to make them real.

McCann's author metaphor is not without its merits, however. I'd like to explain why.

What I'm proposing is that nothing can even conceivably exist unless it is either a mind or the product of a mind. As John McMurray pointed out in "The Self as Agent" and "Persons in Relation", even the language we use to describe the behavior of matter (e.g. "attraction") is inescapably mentalistic. Thus the notion of a mind-independent reality makes no sense. God, who is the Uncaused and Unbounded Intelligent Being, exists at the highest level of reality (call it Level 2). The world and all its creatures (including us) are ideas of God: to be precise, creatures are entities in an interactive novel composed by God. These entities exist on Level 1. Their natures and causal relations are fully specified, and they are also suitably individualized in space-time. However, although their natures are fully specified, their actions are not: the intelligent agents in this interactive novel are free to defy their Maker. Thus in the novel of human history, the details of the plot have not been written by God. We write them, whenever we make choices. As author of the novel, however, God has control over the beginning (i.e. the creation of the world) and also the broad outlines of the ending: in the end, good has to triumph over evil, virtue has to be rewarded, vice has to be punished, and the New Heaven and the New Earth have to be established. The rest of this interactive novel is largely up to us.

Finally, the incompletely specified Pickwickian characters in the stories that human beings write (e.g. Harry Potter, whose house isn't fully specified in J. K. Rowling's novels) exist on Level 0. The relation of human authors to their characters is not quite the same as God's relation to us. While we can write stories whose characters interact with each other and even (if we wish) with their author, our characters lack the autonomy of will (big-L Libertarian freedom) that human beings possess in their relation to God, their Maker. Our characters cannot defy us. They are not real, because they are incompletely specified.

The attraction of this picture, as I see it, is that it dispels a conundrum surrounding creation ex nihilo. Let's try a humorous experiment: imagine a particular (and as-yet non-existent) entity – say, a flawless 40-carat blue diamond sitting on your desk – and try to wish it into existence. Close your eyes, and think hard. Concentrate! Now open your eyes. Did you succeed? No. But here's the funny thing: God made you and me and everything else simply by wishing it into existence: "Let there be light." So my question is: if we can't wish things into existence, how come God can? And my very simple answer is that we can wish things into existence, but only in novels of our own creation, on Level 0. The world, which is on Level 1, is God's novel; the things in our world are products of His mind, not ours.

Some philosophers say that only God, who is Pure Being, can impart being to an essence. But just as a magnetized object (e.g. an iron nail) can be used to pick up other magnetic objects (e.g. a paper clip), a creature like me who participates in God's Being should be able to impart small-b being to something that I wish to create ex nihilo, so long as I'm "plugged into" God. But I can't.

Or perhaps God can wish things into existence because only He is infinitely powerful? Perhaps our wishes are only 10-amp wishes, but God's are infinity-amp wishes, which alone can bring a non-existent thing into being? But the problem here is not the strength of the wishes; it's the fact that wishing, per se, accomplishes nothing in a world which is independent of you. It can only make something happen in a world which vitally depends on you. And the only world which vitally depends on its Maker is one which is an intellectual product of its Maker – i.e. a story. I can only create things within the stories I compose; and God can only create things within His Big Story: the cosmos.