by

Iraj Bashiri

copyright 1999, 2003

Background:

The word "Tajikistan" is a compound of -istan meaning "place of" and tajik, a form with uncertain etymology. The most logical interpretation posits it as the designator used by medieval infidel Turks to refer to the Muslims (Arabs and Iranians) of Central Asia. With the departure of the Arabs, especially after the Mongol invasion, the Iranians of the region became the sole holders of the designation. Another interpretation posits the Persian merchant class as the true Tajiks. Present-day Tajiks relate the name to the Persian word taj (crown). In their interpretation, Tajik refers to royalty or a people of royal standing. The Tajik flag (see below) illustrates this latter interpretation.

At the turn of the 20th century, the region that today is called Tajikistan was called Eastern Bukhara. It was a backward area of the Emirate of Bukhara, a mountainous region, ruled by the Turkish governors of the Amir of Bukhara. In 1920, the Red Army ousted the Amir, who fled to Afghanistan. His people, the Tajiks, were assigned a new rulership chosen from among the leaders of the newly-formed republic of Uzbekistan. In 1924, recognized as a people, the Tajiks were given their own republic with its capital at Stalinabad (the Soviet name for Dushanbe). In 1929, the republic was awarded Union status.

The Tajiks gained their independence from the Soviet Union on September 9, 1991. Celebrating this day has become a tradition in the republic. Since 1991, there have been three government changes and a five-year civil war between the pro-democracy forces and those who intend to set up an Islamic government in Tajikistan and, indeed, in Muslim Central Asia.

In 1997, the rival factions signed a peace agreement which, when it went into action in 2000, divided the authority in the republic among several competing warlords. The survival of the republic depends on the alliances that the factions create among themselves and the funds that are contributed by foreign powers for the reconstruction of the devastated economy of Tajikistan. Otherwise, the food and energy shortages will grow worse and the long list for housing will become even longer.

Geography

| Located in the center of Asia with an area of 55,300 sm (143,100 sk), Tajikistan borders China to the east, Afghanistan to the south, Uzbekistan to the west and northwest, and Kyrgyzstan to the northeast. The country is divided into four distinct regions. | |

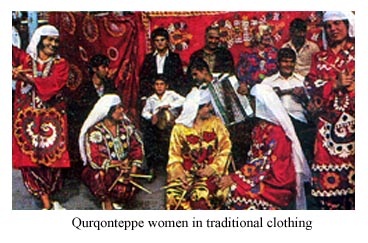

To the northwest is Leninabad, centered on Khujand, the republic’s industrial hub, and until recently, its political hub as well. Khatlan, in the south, is gradually replacing Leninabad as Tajikistan's political center. Khatlan is composed of the two major, relatively independent, regions of Kulab and Qurqanteppe. The third or Central district is composed of Hissar, Dushanbe, and Gharategin. The fourth, Gorno-Badakhshan, is centered on the town of Khorog in the east southeast. The Islamic movement in Tajikistan is supported by Gorno-Badakhshan and Gharategin with nominal assistance from Hissar and Qurqanteppe. |

|

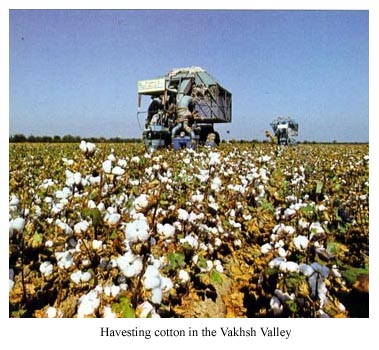

About 93% of Tajikistan is mountainous, at least 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) above sea level. Most settlements are located in three valleys–Ferghana, shared with the Uzbeks; Hissar; and Vakhsh, shared with the Kyrgyz. Most of the settlements are at the height of about 3,000 feet (1,000 meters). Rivers, taking source in the Turkistan, Zarafshan, and Hissar Alai ranges, create favorable ground for agriculture, especially cotton. Some peaks in Gorno-Badakhshan reach 23,000 feet (7,010 meters). Wild flowers abound in the valleys. Marco Polo sheep, yak, and snow leopard are found in the higher elevations.

Climate

Tajikistan's climate is varied depending on elevation. The average temperature in winter ranges between 36 F ( or 2 C) in the valleys and -4 F (or -20 C) in the highlands. In the summer the average readings are 86 F (or 30 C) in the valleys and 32 F (or 0 C) in the highlands.

Tourism

|

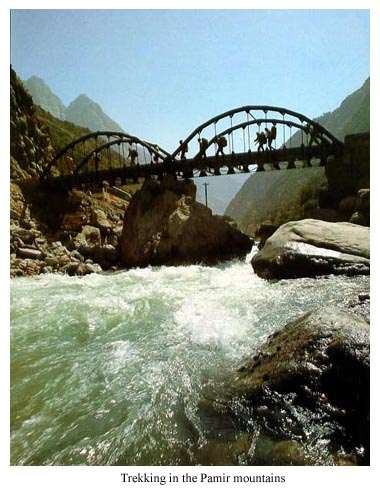

Tajikistan has some of the most wonderful and memorable tourist spots. The Varzob Valley near Dushanbe is the first place to which visitors are taken. Hardy western mountaineers and travelers, however, are attracted by the Pamirs, especially its Peak Lenina, Peak Kommunisma, and Peak Korzhenevskaya in Eastern Badakhshan. In alpine mountaineering, rock climbing, walking, and fishing no place can compete with Tajikistan. Sadly, Tajikistan's tourism suffered a great deal during the Tajik civil war. In fact, most of the major places of interest continue to be out of reach. Museums, parks, and exclusive galleries compensate by introducing the visitor to the various arts developed by Tajiks since their ancestors chose these regions to settle in many centuries ago. |

History

Historically, after the breakup of the Indo-European family, the Aryan branch subdivided so that the Medes and the Pars migrated to the Iranian plateau where they created the Median and Persian Empires, respectively; the Sughd and the Hind migrated to the Aral Sea region. Subsequently, the Hind migrated southeast and occupied the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. The Sughdians settled the region around Samarqand between 1,000 and 500 BC. During the reign of Darius I the Great (BC 522-486) of the Achaemenian dynasty they were incorporated into the Persian Empire. In the fourth century before Christ, the Achaemeninas lost Sughdia to Alexander the Great of Macedonia. The Arabs conquered Sughdiana in the early AD 600’s. Under Muslim rule, especially with Samanid support, Sughdiana grew to encompass Maymurgh, Qabodian, Kushaniyya, Bukhara, Kish, Nasaf, Samarqand, and Panjekent, each a virtual kingdom.

The Tajiks came into prominence as a people under the rule of the Samanids (875-999) who undermined Arab rule and, to a great degree, centralized the government of the region. They also revived the ancient urban centers of Bukhara, Samarqand, Merv, Nishapur, Herat, Balkh, Khujand, Panjekent, and Holbuq that, in turn, elevated the socio-political, economic and, necessarily, cultural dynamics of the new and progressive Samanid state. Additionally, the Samanids introduced a major program of urbanization, a new civic administration, and a revival of traditional local customs. Furthermore, the Samanids allocated resources for public education and encouraged innovation and enterprise. In short, they created a civilization that, in many respects, was unique for its time.

The Samanid revival also benefited the sciences, especially mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Geography, historiography, and philosophy, alongside literature, cultivated the social aspects while mining, zoology, and agriculture contributed to the economy and the well-being of the State. Only a few rival the fame of al-Khwarazmi, the author of Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wa al-Muqabilah in the history of medieval mathematics and the theory of numbers. Just a mention of the word "algebra" is sufficient to conjure up the milieu to which al-Biruni, Ibn-i Sina, Sijzi, and Buzjani contributed. Both al-Biruni and Ibn-i Sina were involved in the field of physics as well. The former excelled in the practical aspects of physics while the latter contributed to the theoretical dimensions of the same. The physicist par excellence of the era, however, was Muhammad Zakariyyah al-Razi, the founder of practical physics and the inventor of the special or net weight of matter. Other contributors to physics were Ibn-i Sina (acoustics), Ibn-i Haitham (optics), and al-Biruni (the completion of the efforts of al-Razi in determining special weights).

Medicine was the first of the Greek sciences to attract the attention of Muslim scientists. The history of medicine in the region, however, dates back to pre-Islamic times when, in AD 529, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian closed the Plato Academy that worked under the direction of Precleus. Seven Roman scientists, who did not have an academy in which to work, were invited by Khusrau I Anushiravan to Iran to carry out their research in the newly-founded University of Gundishapur. The forte of the researchers of the University of Gundishapur, which continued into Islamic times--until the middle of the ninth century--was medicine.

Finally, the promotion of the arts and sciences led to the institution of new centers of learning such as madrasahs built on the model of the University of Gundishapur. It also led to the creation of centers for storing and retrieving information such as the Sivan al-Hikmat in Bukhara. These were libraries that contained manuscripts spanning translations from Greek and Syriac languages on aspects of philosophy to innovative theories of contemporary scholars such as Ibn-i Sina and al-Biruni.

Two major factors contributed to the demise of the rule of the Tajiks. The rising power of the Turks, originally slaves and later commanders in the army of the Samanids, as well as the rise of the Mongols impacted the lives of the Tajiks immensely, especially the Mongols who, in 1220, overran Central Asia and devastated the region. Whether the Tajiks would have been able to weather the tide of Turkish ascendancy and recapture the glory of the Samanid days remains a matter of speculation.

During the Mongol rule (1219-1370), agricultural development and urban expansion were halted, local traditions of kingship were dismissed, and the Shari'ah was replaced by the Yasaq (the decree of Chingiz Khan). Indeed, the Yasaq was used to enforce anti-Muslim policies, discouraging the Central Asian elite from rebellion against the Chaghatai khans. Tajiks who could not tolerate the intensity of Mongol rule either migrated abroad or lived in isolation in the highlands.

The fortunes of the Tajiks declined when the Golden Horde was dissolved and its constituent tribes joined the Oguz Turks who had settled in Transoxiana as early as the 10th century. Rather than settling on the fringes of the urban areas as they had on the Qipchak plain, the new invaders wrested the Tajiks' farms and became farmers. Leaving their cultural centers of Samarqand and Bukhara, the Tajiks continued to take refuge in the highlands in the south. Thus, during the Shaibanid, Astarkhanid, and Manghit rule, Tajik cultural domination declined to the point that in 1920 the Tajiki language was discontinued as the official language of the Emirate of Bukhara.

The Uzbeks, however, were not the only intruders. Russians, after Amir Muzaffar's defeat in 1868, dominated both the Turks and the Tajiks. Indeed, the Turks served as governors and tax collectors for the Russians. In 1924, the Soviets divided the Tajik population between the Autonomous Republic of Turkistan and the People's Republic of Bukhara. The Tajiks, however, continued their struggle to gain independence. In 1924, Stalinabad became the capital of Tajikistan.

Between 1929, when Tajikistan SSR, centered on Stalinabad, came into existence, and 1970, Tajikistan underwent intensive Sovietization, which by necessity accompanied the type of education compatible with carrying out collectivization and industrialization. As was the case in the other republics of the Soviet Union, the individuals with nationalistic tendencies were purged.

The building of the new socialist republic began in earnest in the early 1930’s. In the early stages, a casual observer would not perceive the change immediately. Much of the ancient Emirate of Bukhara continued to resist change. Besides, many peasants preferred the plow to the tractor and many others advocated a return to the old ways. Their numbers, however, were decreasing, as were the numbers of their donkeys, mules, and carts that carried the fruits of their labor to the town and city markets.

By the early 1930's, there was no question in anyone's mind that Tajikistan was on the way to becoming a modern republic with a growing industrial base in the north and a burgeoning agricultural enterprise in the south. The record of production of devoted Tajik workers, driven by ideology, confirms this view. The record includes 2,200 units of labor and 19 Machine Tractor Stations (MTS) with 1,284 tractors. It also indicates that annual cotton production expanded from 38,000 tons (1928) to 50,000 tons (1932). In fact, at the level of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan became the sole source of daraznakh cotton. Opening a combinat for shahibafi in Stalinabad rewarded the Tajiks’ hard work. The combinat created more work and more jobs; with the addition of the Termez-Stalinabad railroad, it also boosted commerce.

|

The combination of ideology and hard work paid off. The net income of the inhabitants rose from 65 million sums [soom] to 112 million sums within a short time. These concrete gains were further rewarded by Moscow with the granting of independence from Uzbekistan in 1929. Furthermore, with assistance from the Center, Tajikistan entered an actual production phase, i.e., it could produce fuel, foodstuffs, textiles, and construction materials. The construction of a major brick factory in the city of Stalinabad in 1932 was the Tajiks' first taste of partial economic independence. They had built, and, therefore, owned, the republic's first construction materials center. |

During the 1930's, Tajikistan underwent a profound transformation. It gradually changed, from a collection of medieval cities, rural towns, and qishlaqs (villages) into a republic with a considerable industrial and agricultural economy. The people, too, changed from a predominantly rural mind-set to a more urban mind-set. Many left their ancestral lands in the qishlaqs for jobs in the towns and cities. The Tajik government that orchestrated the change had also created the means by which to build the infrastructure required to accommodate the plant workers.

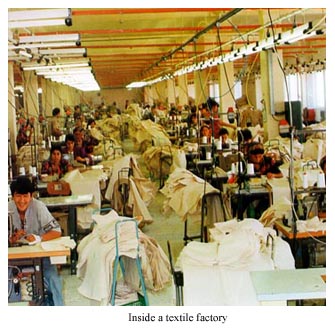

The growing needs of agriculture required the generation of more and more electric power. In the south, the Varzob Hydroelectric Station and a series of lesser stations at the rayon level were completed and went into operation. This also allowed, in 1937, for the planning of the first mechanized textile factory (kombinat-i bafandegi-i dushanbe) to be built in the city of Stalinabad. In addition, by 1938, another 45 Machine Tractor Stations, with 3,217 more tractors, were added to the work force. With the development of the Vakhsh Valley, and the institution of several more kolkhozes and sovkhozes, rural Tajikistan was transformed into an agro-industrial republic, leaving only traces of its feudal past.

A growing nation is always in need of upgrading its agro-industrial base, and Tajikistan was no exception. As foreseen in the 1927 all-Union plan for the region, it was necessary that it slowly move from a light industry region to a more heavy-industry-oriented complex. As a result, more hydroelectric stations dotted the Varzob River and the Kuhistan region in the south. More importantly, the entire region became an exclusive cotton production center equipped with its own small textile and local industries. Additionally, by 1942, 51 Machine Tractor Stations with 3,844 tractors were added to the work force.

The 1940's saw a deep gap within Tajikistan between the socialists and the Wahhabi Muslims. Entire regions, like Tavil Darra, Gharm, and the lower Vakhsh, all the way to Qurqanteppe, chose to respect their ancient traditions of land management and the Islamic way of life. Like the Amish in the United States, they stayed clear of all technological developments, continuing their existence as if the Soviet Union did not exist. They instituted their own schools, hired their own teachers, and organized their society with the help of their muysapeds (elders) and ishans (religious personages).

Ignoring this militant minority, the Soviet Union, which had entered World War II, continued its projects. To meet the nation's need for grain, cotton, fruits, and vegetables, it expedited the completion of the Hissar Canal, which was completed in 1940. To safeguard against mass protest in the face of difficulty, it also allowed moderate improvement in the lives of selected groups of Tajiks, especially those who had been allowed to participate in the work force and who contributed to the building of socialism. Many members of this population were Sovietized Muslims. Additionally, in the early 1940's, while the War raged on, 233,000 houses, many schools, health centers, and recreation areas were built and given to deserving families. Furthermore, to eliminate joblessness, in 1942, the kombinat-i bafandegi-i dushanbe and a new cement factory were put into operation.

The 1940's saw two entrenched ideologies in Tajikistan. Socialism, the dominant ideology, had the upper hand. Able to provide food stuffs, shelter, jobs, and security, it won many of those, who had wavered, to its cause. According to Soviet sources, by this time socialism was fully established in the farthest qishlaqs of the Kuhistan. To a degree, this claim can be justified by the speedy process of urbanization required to accommodate the large number of villagers who came to the cities in search of work in the factories.

|

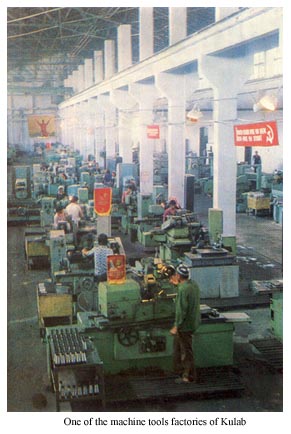

Just the number of buildings created for the institutions of higher education, including Tajikistan State University in the Name of Lenin, which was completed in 1948, further attest to that. Access to knowledge, however, remained limited. Rather than meeting future Tajik needs by training Tajiks who would occupy some of the positions thus far held by European Soviets, more and more factories and low-level jobs were created. These included the Tricotazh factory and the Armiture (armatura) factory named after S. Arjanikidze, in Dushanbe. Additionally, six new Machine Tractor Stations were added, increasing the number of tractors from 3,884 in 1940 to 4,111 in 1950. Skilled workers needed in cotton processing factories in Qurqanteppe and Kulab were brought in from elsewhere in Russia or from the European parts of the Soviet Union. |

The other entrenched ideology in Tajikistan of the 1940's was Islam in its Sunni, Wahhabi, form. As mentioned, these nonconformist Muslims chose the rather inaccessible river valleys of the upper Vakhsh for settlement and virtually cut themselves off from mainstream Tajik life. Were it not for the war, they would have continued their seclusive existence for a much longer period. But, as fate would have it, Soviet authorities needed assistance for the war effort from all the inhabitants of the Union, including the extremist Muslims. Not so much in Gharm and Tavil Darra, but in major cities and towns of the republic, maktabs opened, some mosques were rehabilitated, and four directorates for overseeing the affairs of the Muslims were established in Ufa, Tashkent, Baku, and Makhach-Kala. In exchange, the Muslim clergy allowed Muslim women to work in the cotton fields, Muslim men to undertake behind the front activities, and Muslim youth to participate in the War in whatever capacity they were assigned.

In the early 1950's, improvement of aspects of industry, including mining, fuel, textile, foodstuffs, and building materials remained a constant. Further improvements in lifestyle, both materially and psychologically, were also given a great deal of attention. This latter was given precedence because of the difficulties that had arisen as a result of the war efforts discussed above. In order to accommodate war returnees, in the south, the building of two new cotton processing factories in Qurqanteppe and Shahrtuz was completed and the textile factory in Dushanbe became partially operational. In fact, more institutions and workshops were established and many existing institutions were updated for the same purpose. These new projects, especially those dealing with agriculture, required an upgrading of the facilities that produced electric energy. To meet this need, a third hydroelectric station was built on the Varzob River, and a number of lesser stations, down river, became operational.

During the latter years of the 1950's, perhaps the most profitable contribution of the decade, i.e., the recovery of marshlands for agriculture, was completed. As a result, large tracts of marshland around Qurqanteppe, Kulab (lower Vakhsh), and Dushanbe (Varzob) were recovered and cultivated. Then, the focus of further development was shifted to the upper Vakhsh, where it remained until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Among the achievements of this phase of Soviet development in southern Tajikistan are the completion of the Sharsharah and the foundation of the Sarband hydroelectric stations (both on the upper Vakhsh).

Regarding society at large, the latter part of the 1950's was a watershed in the building of socialism. In spite of the war, over the past decades, much of the infrastructure required by the agricultural sector--Machine Tractor Stations, tractors, factories, and hydroelectric stations--had all been built and were operational. With a few major land reclamation programs, and the integration of small kolkhozes into larger units, management, too, had improved. For a while, therefore, the intellectual power of the State was unified and focused on the resolution of the problems that impeded the rapid rise of socialism. This included an assault on religions and, in the case of Tajikistan, a reversal of the pro-Islamic policies dictated by World War II.

The Tajikistan of the early 1960's saw the fruition of the efforts expended in the development of the lower Vakhsh region, especially in light industry. The automotive industry responded to the immediate needs of engineers, managers, and farmers. Alongside that, a gigantic hydroelectric station with a capacity of 2.7 million kilowatts of energy appeared on the Vakhsh River. Further automation led to the expansion of irrigation and to the introduction of the brigade system on some 13,615 hectares of land. Manpower was boosted to its limits. The resulting agricultural surpluses raised the Tajiks' purchasing power, benefiting the economy, as well as the government. In fact, agricultural surplus and new commodities, such as furniture made in Dushanbe, formed the basis of an inter-republic trade between Tajikistan and her neighbors.

The actual era of prosperity, however, is the latter part of the 1960's. At this time, the production of automotive tools, electricity, and foodstuffs boosted both light industry and trade; naturally, it also improved the lifestyle of the individual Tajik tremendously. Labor input and output increased twofold. Over one hundred new factories, plants, and workshops were added to those already in existence. These included the hydroelectric factory on the Vakhsh, the "Pamir" refrigerator plant, the Hissar Hydro-zal, and the inauguration of mining in Anzab. Furthermore, the production of cotton, milk, meat, and grain increased manifold, and 54,000 hectares of new land was reclaimed. Additionally, a major contribution of the decade, the largest irrigation system in the Kuhistan, i.e., the Yavan-Abkik Irrigation System, was completed. This project brought very large tracts of land into cultivation. The other major contribution of the decade was the kombinat-i bafandegi-i dushanbe, which had become fully operational some time earlier; in 1966, it was included among the textile production outlets of the USSR.

At the Union level, the march toward socialism continued with an overhaul of the educational system of the republic to reflect the rapid changes in the social life of the people. At the level of the individual, a quarter of the people received new housing, salaries were automatically raised, and life conditions, in general, improved in a meaningful and substantial manner.

The major contribution of the late 1960's and early 1970's was the establishment of the Regional Productions Complex in Tajikistan (RPCT). The largest productions center in Central Asia, RPCT was also one of ten such major production centers in the former Soviet Union. These complexes were located mostly in the eastern parts of the former USSR where natural resources were abundant. The complex was especially mentioned in the proceedings of the twenty-fifth meeting of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Covering over 34,000 square kilometers, the complex was limited to the north by the Leninabad oblast' and by the Hissar mountain range; to the west by the Republic of Uzbekistan and the Babataq range; to the east by Gorno-Badakhshan (Badakhshan-i Kuhi) and the Hazrat-i Shah range; and to the south by Afghanistan; and the Panj and Amu Rivers.

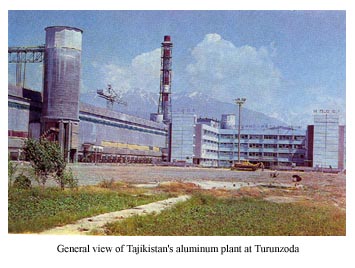

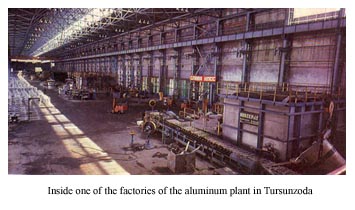

The RPCT served as a framework for future progress in the Kuhistan region for the Soviet Union and, in a general way, for Tajikistan as well. It was mandated, following the directive of the 1971 meeting of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, that the following three units, the Narak Hydroelectric Station, the Yavan Electrochemical Station, and the Tajikistan Aluminum Plant, were approved as the cornerstone of a major complex with the potential of realizing the dreams of the original planners, i.e., the integration of agriculture and industry in a harmonious manner, while, at the same time, controlling the main body of Tajikistan's economy. |

|

| Required by the rapid development of the Soviet Union as a whole, and the demographic projections of the time, especially for Central Asia, the complex was a virtual necessity. It was built in phases. | |

Phase one concentrated on an upgrading of the existing factories, plants, communication systems, irrigation canals, and water reservoirs. For example, a good portion of the area, especially in the Vakhsh Valley and the Hissar region, had already been developed in the early years of the socialist movement. The task at hand, therefore, was to modernize the factories and mechanize the agricultural sectors that fed them. This included the completion of the three Narak Hydroelectric Stations, the first unit of the Tajikistan Aluminum Plant, the mining operation in Anzab, the Termez-Dushanbe railroad--a must for the smooth operation of the needs of the RPCT--and the gas distribution center of the city of Dushanbe. All these units went into operation at about the same time.

The utilization of much of the unused land had started during the era of the first five-year plan in connection with the Vakhsh irrigation system, itself originally created for the production of mahinnakh cotton. Now, other related industries like oil extraction and textile production were added to make the operation more efficient and, more importantly, to utilize the by-products that otherwise would be discarded as waste. Additionally, still in phase one, it was decided to add a number of new factories and plants that complemented those upgraded and refurbished and that were most urgently needed. Phase one, in other words, made southern Tajikistan self-sufficient and allowed the further implementation of the plan for the creation of the complex.

| Phase two comprised the addition of major stations, reservoirs, and land reclamation schemes that would go beyond republic self-sufficiency and into the realm of exporting energy and other commodities to the neighboring rayons and republics nationwide. Part of the revenue generated by the complex was to be devoted to improving Tajik education, economy, and other aspects leading to complete self-sufficiency and independence.

In the long run, the post-World-War-II boom led to an era of stagnation not only for Tajikistan but for the whole of the Soviet Union. And, as is well known, the stagnation eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and, soon after, to the emergence of the independent Republic of Tajikistan in 1991. |

|

In 1992, the growing Muslim discontent against communist rule erupted into a bloody civil war in the south. The war, which resulted in 40,000 casualties, over 50,000 refugees, and 500,000 displaced people, ended after the UN intervened and after the Opposition members were allowed to participate in the governance of the republic.

The most recent history of Tajikistan consists of assassinations, perennial hostage taking, border conflicts, typhoid and plague epidemics, and food, water and fuel shortages. Nevertheless, in spite of clan wars, regional insurrections, and drug trafficking, the Tajiks have convened six rounds of talks under the auspices of the UN, achieving a semblance of unity.

Culture

Tajik culture places a great deal of emphasis on music, especially the shashmaqam system, which is normally played on a dutar. The hafiz (singer) of the shashmaqam is held in great esteem in all formal gatherings. Similarly, Tajiks respect their learned figures of the past. They place a great deal of importance on Ibn-i Sina, Rudaki, and Firdowsi. Following this tradition, they also treat their elderly, whom they refer to as muysaped (white haired), with great respect. It should be added that esteem for the aged is not due to a particular social standing, but for the experience that they have accumulated over their lifetime.

|

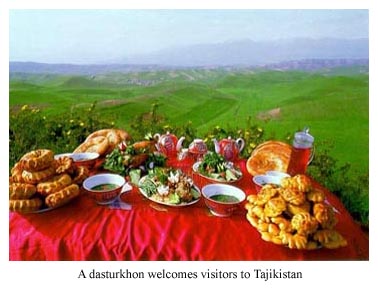

Food plays a central role in the lives of the Tajiks, both within the home and outside. Within the home, food brings all the family members together. It also provides the subject for conversation at the table. The most experienced cook is the one who can prepare the best Aash (rhyms with Macintosh). The dish, made with rice, carrots, and meat is cooked over open fire for close to five hours. |

Outside the house, tea is enjoyed in a chaikhana (teahouse). The chaikhana is the place when men of all ages gather and discuss issues that are important in their lives. Even when they have had their fill of tea, they turn their empty cup upside down in front of them, indicating that they do not wish to be asked to have more tea, and continue their discussion.

The Tajiks also enjoy a game that they have borrowed from their Turkish neighbors. The game is called buzkashi (dragging the goat). In the game, which is played on horseback by very strong opponents, involves the carcass of a goat. The objective of the winner is to drag the carcass throughout the course of the game and throw it in the spot indicated as goal. The champion gains the respect of the people (cf., the hafiz), as well as all the prizes pledged by the organizers of the game.

Natural resources

In addition to cotton, fruits and nuts, Tajikistan’s natural resources include hydropower, petroleum, uranium, mercury, brown coal, lead, zinc, antimony, tungsten, silver, and gold.

Environment

From an ecological point of view, Tajikistan is not a safe place. Imported pesticides are handled without proper ecological expertise. As is well known, such handling of hazardous materials results in degradation of the land and decimation of animals and people. There are also threats of desertification of pastures, loss of water resources, appearance of new viruses and diseases, and appearance of mutations among people and animals. Radioactive and urban waste, especially those accumulating near large cities and in unauthorized places in the countryside are distressing. Many mining enterprises contaminate the drinking water. Storage of waste ore produced by nonferrous metals extraction plants in the river deltas, is yet another source of water contamination during floods. This is not to mention a cement plant that is built at the mouth of the Varzob valley. The plant continuously pollutes the air the capital city.

Natural hazards

The major natural hazards in Tajikistan are earthquakes and floods. The floods are particularly damaging in that they contaminate the water source.

People

Tajikistan, a landlocked country the size of the state of Wisconsin, has a population of 6,863,752. It was forged by the Soviets in the 1920s out of the Tajik-dominated region of Eastern Bukhara. The present configuration is the result of the 1929 inclusion of the Leninabad oblast', i.e., the cultural center of Khujand, into Tajik territory. At the time,

Dushanbe, which now has a population of 800,000, had only 6,000 inhabitants.Nationality

From an ethnic point of view, the Tajiks are Iranian. They are descendants of an Iranian tribe in the same way that the Persians, the Kurds and the Baluchis are Iranian peoples. They were separated from the main body of Iranians after the territories to the east of the Oxus river were permanently lost to the Western Turks. Turkmens and Oguz Turks became a major barrier, discouraging Iranians attempt at contacting their cultural centers on the Silk Road.

Similarly, after the Soviet takeover, Tajiks were deprived of their major cultural centers of Samarqand and Bukhara.

On the question of nationality as such the Tajiks are attached more to the region where they were born rather than to a nation. They come from Khujand or Kulab or Badakhshan rather than from Tajikistan. In this they resemble the Afghans who come from Qandahar or Bamiyan or Mazar-I Sharif, rather than from Afghanistan. This kind of approach to nationality, of course, is likely to create problems, especially that non-Tajiks form a good part of the republic’s population. The ethnic mix in Tajikistan is: 64.9 percent Tajik, 25 percent Uzbek, 3.5 percent Russian (declining because of emigration because of the Civil War), and 6.6 percent other.

Health Care

Before the advent of the Soviets, Tajik health care was in the domain of the hakims, learned individuals who practiced what is known as Unani or Greek tibb (medicine). Such things as lumps of wax for broken bones and prayer scrolls for other ailments were quite frequently used.

During the Soviet era, Tajik health care was developed alongside the health care of the other republics and was subsidized by the government. Tajik doctors and nurses worked in hospitals and clinics using the techniques and medicine made available through the Soviet system.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the combined effects of the collapse of the economy and the civil war destroyed the Republic's infrastructure, including advances in medical care. Suddenly, nutrition, water, sanitation, pharmaceuticals, doctors and nurses were no longer as easily available as they had been during the Soviet rule.

Today, in spite of budget difficulties, the state provides primary health care free of charge. Obviously, the donations of the Red Cross and the other international aid organizations will not flow into Tajikistan ad infinitum. It is up to the Tajiks to use this seed money to generate funds for the welfare of their society through their own economy. Respiratory and cardiovascular conditions, as well as infectious, prenatal, and extragenital diseases are prevalent. In 1998, the infant mortality rate reached 115 deaths per 1000 live births. Life expectancy is 61 (men) and 71 (women) years.

Education

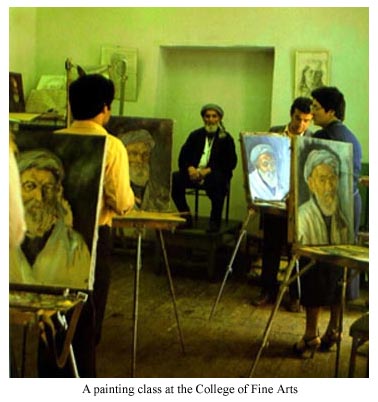

Tajik education in pre-Soviet times was predominantly in the hands of the ishans (religious figures) who headed the maktab and madrasahs in the major cities. The mosque mostly subsidized that education, which concentrated on the study of the Qur’an and hadith. During the Soviet era, too, education was free. The type of education that the Tajiks received, however, was different. Rather than on the Qur’an and the hadith, it was centered on western methodology and scientific subjects.

|

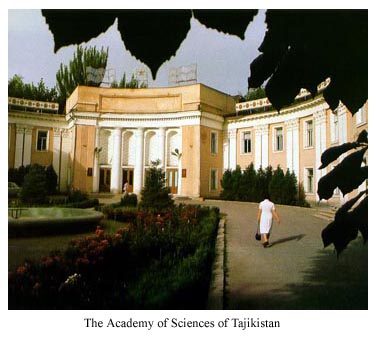

Between 1992 and 1997, Tajik education was decimated. The war destroyed almost all the schools and scattered most teachers who either joined the war effort or left the country. Schools and libraries lost their function and purpose. At the present, compulsory education age is seventeen (in theory) and fourteen (in practice). Continuing the tradition established by the Soviets, the republic continues to enjoy a high literacy rate of 98 percent. Tajikistan’s major institutions of higher learning are the Academy of Sciences of Tajikistan, the Dushanbe Pedagogical Institute, the Technological University of Tajikistan, and Tajikistan State University. |

|

Welfare

Throughout their history, Tajiks have drawn on their own resources for subsistence. They live in large families and share the fruits of their labor. Modern times, however, have interfered with the system on which family members survived without need for outside assistance. The 1992 civil war impacted the family system especially hard as many young, and not so young; Tajiks were killed, leaving their families to take care of themselves. The war also destroyed the insurance-based system on which the Soviets drew for Tajikistan's welfare funds.

After the war, in spite of the difficulties with which the republic's welfare system is faced, most of those who were sustained by the Soviet system remain eligible for aid. Women, for instance, receive a three year maternity leave and monthly subsidies for their children. There remains a large number, as many as 80 percent of the population that lives below the poverty line.

At the present, Tajikistan's welfare is funded by a two percent tax on retirement funds and workers' monthly salaries. Salaries in the republic are generally low; therefore, most workers fail to pay the tax. Until it reaches self-sufficiency, which is some time in the future, Tajikistan's welfare needs to be funded by international donations.

Housing

Tajiks are predominantly a settled people who lived in private homes called havli. There are, however, small communities in far-off areas, especially on the border with Afghanistan, that live in tents. After the advent of the Soviets, efficiency apartment blocks replaced the havlis and the idea of extended family life was modified. Some communities were moved from their villages to apartments on industrial sites where they were educated in the use of modern techniques of mechanized farming and industrial management.

|

Taking advantage of privatization, young Tajiks today are remodeling their old ancestral havlis or are buying new dwellings. Since 1990, the government has built 18,000 units in the south, where the civil war had destroyed over 35,000 homes. International organizations working in Tajikistan have added another 21,000 units. Finding housing in the urban centers is quite difficult. There are long waiting lists for accommodation that becomes available very sparingly. |

|

Religion

The official religion of Tajikistan is Islam. The majority of the Tajiks (85 percent) belong to the Hanafi school of the Sunni sect. Nearly 5 percent of the Muslim population belongs to the Shi'a sect of Islam. The majority of Tajikistani Shi’a belongs to the Isma’ili sect. There are also some Russian Orthodox and some Lutheran Christians. In 1990, the Jewish population of Tajikistan was estimated to be 11,500.

Although the Tajiks are Hanafi Sunnis, towards the close of the last century there was a resurgence of Wahhabism in the republic. Wahhabism is a subsect of Hanbali Sunni sect, the strictest in adhering to the rules of the Shari’ah. Most of Tajikistan’s energy in the past decade has been exerted in the direction of keeping the Wahhabis from overthrowing the government and installing an Islamic republic.

Language

The official language of Tajikistan is Tajiki (also referred to as Tajik). Before 1924, it was written in Arabic letters. In 1929, a Latin alphabet was devised and used instead of the Arabic. In the 1940’s, Latin was replaced by Cyrillic, which continues to be used as Tajikistan’s official script today. After independence an attempt was made to revive the Arabic script. But mounting social, political, and economic problems have prevented the change from being realized.

Russian, which before independence was the official language, is now the language of inter-ethnic communication. It is also used in international affairs, as well as in government and business. Although on the surface Russian might seem to be demoted, in practice, it is the language with the power. Unless equipped with a sound knowledge of Russian, it would be very hard for a Tajik youth to find a job in the administration or in fields that deal with technology or science. Uzbeki is spoken in Khujand and Qurqanteppe and Kyrgyzi in the highlands close to the Kyrgyz border in Badakhshan.

It should also be noted that the Badakhshan region of Tajikistan has some of the least touched remnants of the Iranian languages of the region. The article entitled the Languages of Tajikistan in Perspective deals with this aspect of Tajikistan’s linguistic scene.

Government

The name of the country is the Republic of Tajikistan. The capital of the republic is called Dushanbe (lit., Monday, on account of the Monday bazaar held there at the turn of the 20th century).

In May 1992, a Majlis (assembly) with 80 members, replaced the Supreme Soviet. The office of the president was abolished. The head of the Majlis served as the head of the government until 1994 when elections for president were held.

|

Administratively, the republic comprises 2 provinces and one autonomous province. The Constitution of the republic was ratified on November 6, 1994. Tajikistan’s legal system is based on the civil law with no judicial review of legislative acts. Suffrage in Tajikistan is at 18 years of age. The judicial system, very much in the tradition of Soviet system, consists of courts at city, district, region and republic levels. The same hierarchy is repeated for the organization of the military courts. |

The Executive branch comprises a chief of state or president, a head of government or Prime Minister, and a cabinet or Council of Ministers appointed by the president with the approval of the Supreme Assembly. The President appoints the Prime Minister. Per a constitutional referendum that was held on June 22, 2003, the office of the presidency is for two seven-year terms.

The legislative branch comprises a bicameral Supreme Assembly consisting of two chambers. The Assembly of Representatives (lower chamber) has 63 seats. The members of the lower chamber are elected by popular vote to serve five-year terms). The National Assembly (upper chamber) has 33 seats. The members are indirectly elected, 25 selected by local deputies, 8 appointed by the president; all serve five-year terms.

The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court; the president appoints the judges.

Political parties

During the years after independence, Tajikistan had up to seventeen political parties vying for power. Today, the number of parties is much smaller. The major parties are the Democratic Party of Tajikistan, the Islamic Revival Party, the People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan, the Social Democratic Party, the Socialist Party, and the Tajik Communist Party of Tajikistan. Additionally, there are also two unregistered political parties with 1,000 or more members. They are the Progressive Party and the Unity Party.

Flag

| Adopted November 24, 1992 three horizontal stripes: red over white over green centered on the white, a gold crown with seven stars above it. The ensemble represents state sovereignty; unbreakable unity of workers, peasants and intellectuals; and friendship and brotherhood among all nationalities. |

Democratization

General Introduction

In order to understand the economy of the republics of the former Soviet Union, it is necessary to understand how centrally controlled economies work and how a centrally controlled economy is changed into a market economy.

In simple terms, the Communist Manifesto gave birth to a number of economies in Central Asia all of which were controlled by the state. The articles of the Manifesto asked for a total, central control of all aspects of life. In other words, all the peoples’ assets were taken from them and placed under the supervision of the State. This included the factories, plants, and natural resources, as well as human resources.

Privatization is the reverse of centralization. It requires a centrally controlled state that wishes to become a modern independent state to decentralize its agriculture, industry, businesses, and housing. It requires that the individual be given the right to buy and sell property. Means of transportation, production, and communication should be placed in the hands of the people. Similarly, the state should decentralize its banks, allow foreign investment to help develop its resources, and become a party to local and international efforts in running a meaningful and profitable market economy.

A truly independent republic cannot ignore freedom. It must allow its population the right to free speech by placing the media (newspapers, radios, and televisions) in the private domain and by removing censorship. Additionally, people should be given political freedom so that they can form political parties, stand for election, and vote.

What was outlined above serves as the basis for creating a democratic state with a stable government. A republic with a parliament that respects international law and which legislates laws that are sensitive to ethnic, racial, ideological, national, and gender concerns of the people, a government that recognizes equal opportunity and equal rights of its people.

Finally, an independent state must create access to education and health care through state and private welfare programs, it should form committees to oversee its conduct of human rights, as well as a committee to handle abuse of natural resources.

Since receiving their independence, the republics in Central Asia have responded differently to the demands of independence, especially with respect to privatization, political freedom, and human rights issues. The difficulty does not rest with the republics as much as with the nature of changes that are required of them. Obviously these changes cannot be meaningfully implemented unless those receiving the changes are cognizant of the rules of democracy. As every one knows, the road to democracy is long. It requires sacrifice as well as a large amount of funds for educating the people and making them understand the working of the law vis-à-vis the rights of the individual and the community.

Economy

Tajikistan’s economy is based on agriculture. Originally using traditional means of production, in the 1930’s, Tajikistan’s agriculture became mechanized. Huge stretches of land, especially in the south, were devoted to cotton monoculture. In the 1960’s, agriculture and industry were combined to create in southern Tajikistan, one of the largest agro-industrial complexes in the former Soviet Union. Once operational, the complex boosted Tajik economy and created a wonderful life. Thousands worked in its plants and factories and thousands were engaged in trade related to the products created in the plants of the complex. The aluminum factory that forms the core of Tajikistan’s economy today dates to that economic boom.

Between 1992 and 1997, Tajikistan was in turmoil. It so happens that the agro-industrial complex outlined above was located at the hub of the conflict between the Muslims and Communists in the south. The complex was destroyed as were the fields that supported it. Before long the field workers migrated to the cities to work there and the plants and factories were abandoned.

For a number of reasons, Tajikistan’s economic situation is fragile. These reasons include problems of money transfer in and out of the country, uneven implementation of structural reforms, weak governance, and a heavy external debt burden. In 2002, servicing of debts owed to Russia and Uzbekistan alone required 50 percent of the government's revenues. To this can be added corruption, natural disasters, presence of paramilitary troops, and armed criminals.

Agriculture

| Agrarian Tajikistan has had a difficult time adjusting to modernization, a process that began after the defeat of the Basmachi movement in the 1920’s. Even then, when the Soviets reluctantly decided to allocate funds for the collectivization and industrialization of the republic, the story of Tajikistan's economy has been one of boom and bust. The boom began in the early 1930’s, when the Kuhistan region in the south was turned into a cotton monoculture concern and the north into an industrial showcase. Between 1930 and 1960, Tajikistan's sovkhoz and kolkhoz farms were mechanized and large tracts of marshland around Qurqanteppe, Kulab, and Dushanbe were recovered and turned into incredibly large fields of cotton. This initial success, between 1960 and 1970, led to the creation of the Regional Productions Complex in Tajikistan (RPCT), one of the Soviet Union's ten major agro-industrial complexes. With the aim of integrating agriculture and industry, the RPCT upgraded all existing factories, plants, communication systems, and irrigation channels and built three major interrelated units: the Narak Hydroelectric Station, the Yavan Electrochemical Station, and the Tajikistan Aluminum Plant. Similarly, in the north, mining operations proceeded at Anzab and in the Murghab region of Badakhshan. |  |

About 94 percent of Tajikistan is mountain and steppe, and only five percent is arable. There is grazing on the slopes of the Gharategin and Pamir mountains, and fishing in the Vakhsh, Panj, and Gunt rivers. Tajikistan's major minerals include silver, gold, uranium, precious stones, and salt. The country's future wealth, however, lies in its potential for the development of hydroelectric power centered on the Vakhsh and Gunt rivers. Today, the Vakhsh complex, developed as part of the RPCT, supplies 98 percent of the energy needs of the republic. If managed properly, the complex can provide energy for export to neighboring republics, especially Kyrgyzstan.

Agriculture, the most important sector of Tajikistan's economy, employs 45 percent of the work force. Tajikistan's agriculture is mechanized and its agribusiness has contributed immensely to the republic's economic recovery after the fall of the Soviet Union. Most settlements in Tajikistan are located in the valleys at about 3,000 feet above sea level. Rivers, taking source in the Turkistan, Zarafshan, and Hissar Alai ranges, create favorable ground for agriculture, especially cotton. Other agricultural products are grain, fruits, grapes, vegetables, as well as cattle, sheep, and goats. Due to a shortage of spare parts, as well as a lack of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, Tajikistan's agriculture is not operating at its full capacity. Once fully privatized, in the distant future, Tajikistan offers one of the best opportunities for investment in agriculture. Tajikistan produces a limited amount of opium poppy for domestic consumption.

Only about five percent of Tajikistan’s land is arable, the other 95 percent is mountain and steppe. The slopes of the Gharategin and Pamir mountains provide very good grazing and there is adequate fishing in the Vakhsh, Panj, and Gunt rivers. Silver, gold, uranium, precious stones, and salt are among the most cited minerals. There is also a considerable amount of coal in Badakhshan. It is the hydroelectric power, centered on the Vakhsh and Gunt rivers, however, that points to the country's future wealth. In fact, 98 percent of the energy needs of the republic comes from the Vakhsh complex, the area which has the greatest potential for providing energy for export to Kyrgyzstan and other neighboring republics.

At the present, Tajikistan’s agriculture is mechanized. It employs 45 percent of the work force and remains the most important sector of the republic’s economy. Were it not for Tajikistan's agribusiness, the republic's economic recovery after the fall of the Soviet Union would not have progressed as it did. Another factor, of course, is the type of agricultural land that is favorable for planting cotton. Tajikistan’s other agricultural products include grain, fruits, grapes, and vegetables.

Animal husbandry, a subset of agriculture, also contributes to Tajikistan’s economic wealth. Cattle, sheep, and goats are among the most cited animals used for food or transport in the republic.

Industry

Although Tajik industry began operation later than that of the other republics, it moved ahead rapidly. In the 1960’s, Tajikistan moved from a light industry region to a more heavy-industry-oriented complex. With a sharp increase in the number of hydroelectric stations, the entire region became an exclusive cotton production center equipped with its own small textile and local industries. The republic's actual era of prosperity was during the latter part of the 1960’s when the production of automotive tools, electricity, and foodstuffs boosted both light industry and trade. Over one hundred new factories, plants, and workshops were added to those already in existence. These included the hydroelectric factory on the Vakhsh, the "Pamir" refrigerator plant, the Hissar Hydro-zal, and the inauguration of mining in Anzab. Furthermore, the production of cotton, milk, meat, and grain increased manifold and 54,000 hectares of new land was reclaimed. Additionally, the completion of the largest irrigation system, in the Kuhistan, the Yavan-Abkik Irrigation System brought very large tracts of land into cultivation. The Dushanbe Weaving Plant was included among the textile production outlets of the USSR. In 1998, nonferrous metallurgy, Tajikistan's main industry, produced 33 percent of Tajikistan's industrial production. Today, as a consequence of a protracted Civil War, Tajikistan's industry is facing problems. The aluminum branch of the industry, which has the potential of producing 517,000 tons of aluminum annually, is operating at only 43 percent of its capacity. The Yaghnab coal deposit has an estimated reserve of 800 million tons of coal. Yet, out of the fifteen industrial coal reserves in Tajikistan only two are operational.

| Today, among the fifteen former Soviet republics, Tajikistan has the lowest per capita GDP. Because of a shortage of chemical fertilizers and manpower, cotton, its most important crop, is not grown to capacity. Additionally, Tajikistan's mineral resources are varied but limited in amount. They include silver, gold, uranium, and tungsten. Precious stones are mined in Badakhshan, but only in amounts sufficient for local use. Tajikistan's industry is centered on the aluminum plant, the hydropower facilities, and the small, but now obsolete factories originally constructed for the RPCT. |  |

Tajikistan's economy serves two markets. A local market, which is supplied with traditional goods produced in the traditional style, and an international market in aluminum and cotton. The international market, although limited in scope, is heavily specialized and industrialized.

Hydroelectric power, generated at a number of points on the Vakhsh and other

rivers, played a major role in Tajik industry, especially when, in the 1960’s,

light industry was changing into heavy industry. Although the republic could

cultivate and harvest cotton, it was not allowed the requisite factories to

process the cotton it produced. It owned only several small textile and local

industries. The bulk of the cotton was shipped out to Soviet outlets controlled

by Moscow. This process proved very costly for the Tajiks when the Soviet Union

broke up and they were left with a cotton surplus and no other commodities,

especially wheat, rice, and sugar.

Privatization

Like the other republics of the former Soviet Union, Tajikistan began privatizing its state holdings in 1992. The process, however, was interrupted in the same year by the outbreak of civil war and was not resumed in a meaningful way until the signing of the peace accord of 1997; although, in 1994, the Council of Ministers of Tajikistan issued a decree on the privatization of State Properties. During 1999, there was a steep rise in privatization. As a result, over 80 percent of residential houses, 4,507 state enterprises, 350 stock companies, and 1,223 enterprises were privatized. Additionally, 1,866 ventures gained the right to own property.

Between 1995 and 1997, Tajikistan was scheduled to reform its legal infrastructure and its agricultural sector, as well as privatize its small-scale enterprises. In other words, Tajikistan was to lay the foundation for international investment. The privatization of large-scale enterprises and the establishment of banking, credit and taxation systems were to follow. By the year 2000, Tajikistan was to be able to modernize its economy, create an efficient infrastructure, and implement large scale socio-economic programs. None of that has happened; not, at least, according to the plan.

Privatization in Tajikistan has created rules of its own. Rather than selling its holdings to farmers, the government insists on maintaining possession of all agricultural land. As of September 1996, farmers can rent plots on a lifetime basis and can pass it on to their children. By 2001, only 261,800 farms were in the private sector. The majority of Tajikistan's farmland remains within the government-controlled kolkhoz and sovkhoz system.

Banking

In 1998, Tajikistan had 28 commercial banks with 205 branches. In 1999, guided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, that number was reduced to 19. The following are Tajikistan's major commercial banks: Agroinvestbank, Tajikbankbusiness, Sberbank, and Vnesheconombank.

Tajikistan's currency, the Somoni, was introduced in October 2000.

Exports and Imports

During the Soviet era, Tajik cotton and aluminum were shipped to Moscow or wherever the decree from Moscow indicated. Exports and imports in the sense understood by market economies did not exist. After independence, however, Tajikistan has made an attempt to open its door to foreign investment and foreign goods. In fact, many Tajiks have abandoned their traditional involvement in agriculture to work in the cities and contribute to trade.

Exports

Tajikistan's export commodities include aluminum, precious metals and precious and semi-precious stones, especially lapis-lazuli. Other exports include electric energy, cotton fiber, fruits, vegetable oil, leather, and textiles. Tajikistan's export partners are the Netherlands, Switzerland, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Tajikistan's total exports in 2001 amounted to $640 million.

Imports

Tajikistan's import commodities include technology, nonferrous metallurgy, petroleum, natural gas, oil products, aluminum oxide, machinery and equipment, flour, and sugar. Tajikistan's import partners are Uzbekistan, Russia, and Switzerland. Tajikistan's total imports in 2001 amounted to $700 million.

Balance of Payment

Tajikistan's external debt was estimated at $1.23 billion in 2000. In 2001, Tajikistan received $60.7 million in economic aid from the United States.

Transportation

In 1990, Tajikistan had a total of 482 km of common carrier service railway; a total of 29,900 km of highways, 21,400 km of which is paved. This latter includes some all-weather gravel-surfaced roads. Tajikistan also has 8,500 km of unpaved roads, mostly made of unstable earth. The Panj River in the south, Tajikistan's only waterway, is not navigable. In 1992, Tajikistan had 400 km of pipelines for carrying natural gas. As of 2001, there are 53 airports only two with paved runways.

Communication

Tajikistan's communication system is poorly developed and even more poorly maintained. In 1997, there were 363,000 main telephone lines and 2,500 mobile cellular telephone lines in Tajikistan. Many of the country's towns are outside the national network and, consequently, are deprived of services. Domestic connections are made by cable and microwave radio relay while international connections are achieved by either cable and microwave radio relay (to other CIS republics), or by leased connections to the Moscow international gateway switch. Intelsat also links Dushanbe to the international gateway switch in Ankara (Turkey) and the satellite earth stations - 1 Orbita and 2 Intelsat.

Military

When Tajikistan gained independence in 1991, it did not have a military of its own. In 1993, the foundation for a military was put in place. At the present, Tajiks can join the military at the age of 18. The military has a total manpower of 1,704,457 of which 1,397,188 are fit for service. The republic spends $35.4 million on its military. Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh forces assist two Russian divisions on the border of Tajikistan with Afghanistan.

Border Issues

Tajikistan has border disputes with China, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Some of the disputes deal with water sharing agreements among neighbors while others are disputes over the location of a particular boundary. In 2002, Tajikistan ceded 1,000 sq km of the Pamir Mountain range to China for which China relinquished 28,000 sq km of Tajik lands. Discussion of boundary disputes with Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan continue.

Tajikistan serves as a conduit for the transfer of drugs from Afghanistan and points east to Russia and Western Europe. The country produces small amounts of illicit drugs for internal consumption as well. Tajik authorities seize a large percentage of the drugs that cross the Tajik border.