by

Iraj Bashiri

copyright 1999, 2003

| Background A major portion of the population of present-day republic of Uzbekistan belongs to the descendants of the Turkish tribes that invaded Central Asia in the eleventh century. A smaller number belongs to the Turkish tribes that were swept by the Mongols into Europe in the thirteenth century and who were forced to retreat before the armies of Moscovy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Some of those tribes relocated in present-day Central Asia, especially in the Samarqand and Bukhara regions The descendants of Khan Uzbek belonged to many tribes. These tribes, upon arriving in Central Asia, set up three khanates at Khiva, Bukhara, and Qoqand. The khanates were ruled by the most prominent chiefs of the confederation. The tribes around Samarqand and Bukhara were ruled by Manghit overlords who ruled supreme until their sovereignty was challenged and overshadowed by the Russian Empire. During the last decades of the nineteenth century until the rise of the Soviet Union, they ruled the region on behalf of the Russian tsar. In 1920, the Soviets abolished the Emirate of Bukhara and, in 1924, created the Soviet Socialist Republic of Uzbekistan. The administrative affairs of the republic, which had traditionally been the domain of the Persians, were placed in the hands of young and progressive Uzbek intellectuals sanctioned by Moscow. An attempt by the tradition-bound Muslim population to create an autonomous government was mercilessly crushed by the Red Army. |

During the Soviet era, the land of the Uzbeks became primarily a source of raw materials for the exploitation of which many factories were established. By the end of the Soviet era, these exploitative efforts resulted in the devastation of both the land and the water resources of the region. The Aral Sea is a glaring example of that.

Like the other republics, Uzbekistan underwent collectivization and industrialization. In the late 1930’s, its population was subjected to purges. In the 1980’s, fraud was discovered in Uzbekistan’s cotton industry. Gorbachev fired the perpetrators, as the Uzbeks paved their way to independence.

Uzbekistan became independent in 1991. Since then the republic has been diversifying its economy, developing its natural gas and petroleum resources, and moving towards industrialization.

A major concern in the republic is the rise of fundamentalist Islam in the Ferghana Valley. Determined to establish an Islamic Caliphate in Central Asia, Hizb al-Tahrir has been recruiting young Muslims into its ranks and has been defying the authority of President Islom Karimov. Although band, the movement continues to recruit young Muslims in not only Uzbekistan, but Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan.

Geography

With an area of 172,740 square miles (447,400 sq. km), the Republic of Uzbekistan is located in the middle of Central Asia. It is bound by Kazakhstan to the north, Tajikistan and Afghanistan to the south, Kyrgyzstan to the east, and Turkmenistan to the west. Uzbekistan has a work force of over eleven million. The Karakalpakistan Autonomous Republic has been a part of Uzbekistan since 1936.

The topography of the Republic is diverse. The Amu Dariya and the alluvial plain of Kizil Kum cover most of the north to the Aral Sea. The south is comprised of the foothills of the Pamir-Altai mountain system and the fertile valleys of the Ferghana, Syr, and Zarafshan Rivers. The Ferghana valley, in the southeastern corner of the Republic, is 300 kilometers long and 170 kilometers wide. It produces 400 types of grapes, but is most well known for its horses. The Amu Dariya, in the west, and the Syr Dariya, in the east, and their 600 tributaries take source in the Tien Shan and the Alai highlands. They feed the Kara Kum Canal and the myriad of waterworks on their way to the Aral Sea. Needless to say that the rivers fall short of feeding the Sea properly to sustain it. The desert has reclaimed a good portion of it and the rest struggles to survive.

Climate

Summer in Uzbekistan is long, dry, hot, and cloudless. In the south, the temperature can reach as high as 104 F. The mean temperature for July, however, is 90 F (or 32 C). Winter is usually short. The mean temperature for the north in winter is 10 F (or -12 C) but some days can be as cold as -36 F (or -38 C).

Tourism

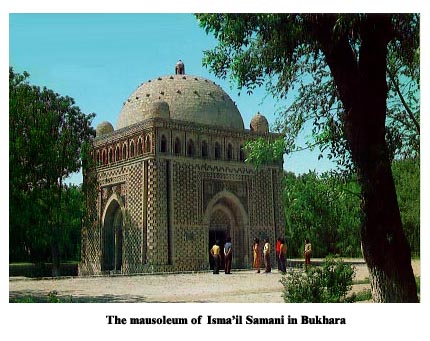

Heir to Islam's most noble cities, Samarqand, Bukhara, and Khiva, Uzbekistan has also a great potential for tourism.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan's tourist industry lost its major supporter, Intourist. Uzbekistan’s tourism industry then consisted of visitors interested in the republic's mountain sports: skiing, trekking, and hunting. After the turmoil in Central Asia subsided, especially after the conclusion of the civil war in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan promoted a revival of the ancient Silk Road. The cities of Samarqand, Bukhara, and Khiva, heir to Islam's most cherished traditions, were promoted to persuade the old clientele, and some new ones, to return to Uzbekistan.

The project was supported by building a number of new hotels and by adding several new sites including "Shakhimardon" in the Ferghana Valley, "Chimgan" and "Yangiabad," near Tashkent, and the Kizilkum Desert for camel rides in the sand. Other places of interest in Uzbekistan are the Gur-i Amir (Tamerlane's mausoleum), Shah-i Zinda (the living king), the Museum of Uzbek Art, the Aibek Museum of the History of the Peoples of Uzbekistan, and the Museum of Uzbek Decorative and Applied Arts. |

|

History

The territory of present-day Uzbekistan has changed hands many times. In the sixth century B. C., it was conquered by the Persians and remained a satrapy of the Persian Empire until the fall of the Achaemenian Empire to Alexander the Great. The Western Turks invaded the region in the sixth century and established Turkish rule beyond Transoxiana during the sixth to the tenth centuries. Between the rise of Islam and the tenth century many Turks in the region accepted Islam. In fact, many became warriors dedicated to the expansion of Islam beyond Central Asia into India and beyond.

The migration of the Turks into Central Asia intensified with the coming of the Oguz Turks in the eleventh and the Seljuq Turks in the twelfth centuries. Subjugating the Persian and Arab populations of the region, the Turks created a viable autocracy that controlled Central Asia, a good part of the Middle East, and Asia Minor.

In the thirteenth century, the region was invaded by the Mongols who swept the populations residing around Lake Baikal, in greater Central Asia, and on the Kipchak Plain into Russia and Eastern Europe. Many of these people were of Turkish origin. In the sixteenth century most of them were pushed back by Russia. They joined their fellow Turks who had made Central Asia their permanent home as early as the tenth century. A portion of present-day population of Uzbekistan belongs to this Turko-Mongol group.

In terms of ethnogenesis, the Uzbeks recognize themselves as the descendants of Khan Uzbek (1322-1342) who converted the Golden Horde to Islam. After the break up of the Golden Horde and the creation of the Khanates of Crimea and Kazan, the Uzbeks broke away from the Khanates and settled in the region between the Lower Volga and the Aral Sea. Then, at the beginning of the 16th century, led by Shiban Khan, they invaded Bukhara, captured Samarqand, Tashkent, and Urgench. The Shibanid dynasty (1500-1600) was the fruit of this bold move of Shiban Khan.

Between 1600 and 1753 the Ashtarkhanids, descendants of Chingiz Khan and Shiban Khan, ruled Bukhara. The Ashtarkhanids practiced religious tolerance and kept good relations with the Shi'ite Safavids of Iran. By the mid-1700s, the dominant Uzbek tribes set up three major khanates in the region: the Emirate of Bukhara, which was ruled by the Manghits between 1753 and 1920; the Khanate of Khiva, which was ruled by the Qunurats between 1717 and 1920; and the Khanate of Qoqand, which was ruled by Qoqan between 1710 and 1876.

Originally, the Uzbeks were made up of 97 tribes. After association with other Turkish tribes (settled and nomadic) and indigenous Iranians (settled Tajiks), three main groups have emerged: the sart, or settled Uzbeks, who form the majority of present-day Uzbek population. They are indistinguishable from the Tajiks and, like the latter, do not have any tribal organization. The second group is known as Turki, or descendants of the Oguz tribes of the 11th-15th centuries. This group has retained its tribal affiliations; its members are known as the Qarluq, Barlas, and others. The third group, the Qipchaq, also has retained its tribal affiliations and has subdivisions such as the Qunqurt, the Manghit, and the Kurama. The Sart Uzbeks have a tendency to assimilate other nationalities. The assimilation of the Tajiks into the Uzbek fold is a clear example. They are also in the process of absorbing the Turki and the Qipchaq by gradually divesting them of their tribal ways and ushering them into the Sart culture.

Culture

Culturally, Uzbekistan is diverse. For centuries, its cities, especially Samarqand and Bukhara, served as the center of trade on the Silk Road. Traditional Uzbek music, national dress, cuisine, and various styles of interior decoration in Uzbek houses reflect this diversity. The Uzbeks wear colorful costumes, especially during the Nav Ruz (New Year) celebration. Men wear a striped robe, a silk kerchief tied around the waist, and an embroidered skullcap, while women wear dresses made from bright shot silk, colorful shawls, and embroidered silk headgear.

Like the Tajiks and the Kyrgyz, the Uzbeks eat a fair amount of rice and pasta foods. Laghman and manti are basically meat and pasta dishes. Perhaps originally Uighur, they are regarded as national food by most of the populations of the republics. Pilav, a rice dish, is recognized from India to the Middle East. In Central Asia, shredded carrots, meat, and onion are added. Hot green tea is served in almost all chaikhanas (teahouses).

|

Uzbekistan is distinct from the other Central Asian republics

in that it not only has the largest Muslim population but, over the centuries,

its cities, especially Bukhara, have served as centers of learning. The

Mir Arab Madrasah attracts students interested in theology from throughout

the world. Similarly, the Uzbek Academy of Sciences, established in 1943,

contributes immensely to the development of the sciences and the arts of

the region.

Natural resources The natural resources of Uzbekistan consist of natural gas, petroleum, coal, gold, uranium, silver, copper, lead and zinc, tungsten, and molybdenum. Natural hazards Many of the towns and villages of Uzbekistan are plagued by sandstorms that take source in the Kara Kurum. At times, entire villages have been taken over by the sand. |

Environment

A major environmental problem, which is now known to the entire world, is the pollution of the rivers and lakes. Another is soil erosion. Diverting the waters of the Syr and the Amu into canals and waterways has affected the Aral Sea so that it has shrunk to a third of its size in the 1950's. The problem is enigmatic in that the livelihood of the people, living around those canals and using those waterways now depends on their existence--the very existence that sucks the life "blood" of the Aral.

The Aral Sea has been shrinking steadily, adding to the desertification of the lakebed and its contamination of the region by exposing DDT, chemical pesticides, and natural salts. These hazardous materials, strewn about by wind, not only contaminate the food chain, water, and air but cause countless human health disorders. This is not to mention a number of buried nuclear waste processing sites that damage the soil.

With the largest population in the region, 25,981,647, Uzbekistan has the following ethnic mix: 80 percent Uzbek, 5.5 percent Russian, 2.5 percent Karakalpak, 1.5 percent Tatar, 5 percent Tajik , 3 percent Kazakh, and 2.5 percent other. In addition, 4 to 6 million Uzbeks live in the neighboring republics of Central Asia so that 23 percent of the population of Tajikistan, 13 percent of the population of Turkmenistan, and 12.9 percent of the population of Kyrgyzstan are ethnic Uzbeks.

Nationality

Nationality to the Uzbeks means something quite different than it does to the Kazakhs. All Kazakhs and Russians living in Kazakhstan consider themselves Kazakhstanis while in Uzbekistan only the Uzbeks are Uzbekistanis. The rest of the population, the Tajiks, Russians, Kyrgyzes, and others are not as easily identified as Uzbek nationals even though they might have lived their whole life in Uzbekistan. There is also a degree of recognition. Tajiks, for instance, due to their claim on the cities of Samarqand and Bukhara are kept from easily achieving Uzbek citizenship.

Health Care

Like its educational system, Uzbek health care, too, was in the domain of religion. Greek medicine (Unani Tibb) accounted for a great deal of the remedies prescribed by the hakims (traditional doctors). Sometimes prayer scrolls were sent home with the patient who was to follow strict rules for their effective preparation. Except for those who were rich, hakims did not make house visits. They could be found at home or in the mosque.

During the Soviet era, the ishans (Muslim holy men in Central Asia) of the past were regarded as charlatans. Medicine was the domain of Russian and European Soviet doctors. Books and pamphlets were published to discredit traditional values, especially those that used religion as a solution for social problems.

Today, the state provides health care with ministries and other authorities in full control. The state of health of the individual, however, depends on the region of the republic in which he or she resides. The rural areas, especially around the Aral Lake, have a higher incidence of disease than the southern regions. Disease types, to a great degree, depend on the mode of living. The rural population suffers from acute infectious diseases like diarrhea and respiratory infection while the urban population suffers from chronic lifestyle-related illnesses, particularly cardiovascular conditions and strokes. The infant mortality rate is 72 deaths per 1,000 births, and life expectancy is 60 years for men and 67 years for women.

|

Education Before the advent of the Soviets, the Islamic clergy organized their educational system. The subject matter in the elementary schools (maktab) was the Qur’an. In advanced theological schools (madrasah), hadith and interpretation of the Qur’an and the hadith were taught. The teachers of the Islamic schools were paid from the zakat (tithe) funds received by the mosque. During Soviet rule, Uzbeks continued to receive a free education. In addition to being funded by the Soviet system, which also controlled the curriculum. The Soviets, however, did not allow the traditional subjects much room to grow. Instead, courses on scientific atheism and on natural sciences were offered. Today, 60 percent of Uzbekistan's population is under 25 years of age. Education, therefore, carries much more weight than in some of the other former republics. Uzbekistan’s literacy rate is 97 percent and education is compulsory up to the age of 15 (full time) and 18 (part time). Over the last decade, Uzbekistan has developed a highly qualified teaching staff. Additionally, privatization has allowed a review of the old textbooks and the addition of new subjects. They also have built new institutional facilities and rehabilitated many of the schools originally built by the Soviets. |

Uzbekistan's institutions of higher learning include the Uzbek Academy of Sciences, the University of Tashkent, Uzbek State University, the Institute of Seismology, as well as many technical and research centers and madrasahs (Islamic theological schools). The official language of the republic is Uzbeki. Tajiki and Russian are also frequently used, the latter primarily for international affairs and business.

Welfare

Before the Soviets, the mosque assisted poor Uzbeks, the disabled, and others in need of communal help. The funds for such assistance were derived from the annual zakat paid by the faithful. Zakat funds also supported many other welfare-related projects, like building schools, mosques, bridges, and communal bathhouses.

Under Soviet rule, an employee’s child care, health care, and housing needs were the responsibility of the employer. Building and maintenance of homes for the disabled and the disadvantaged were the responsibility of those who had benefited from the efforts of that segment of the population in previous years. Depending on contribution to the work force, those unable to work, as well as war veterans were assisted in special homes and sanatoriums. Similarly, price controls empowered pensioners to buy basic consumer goods.

After Uzbekistan became independent, the state took over the welfare system and tried to keep poverty under control. Today, the state guarantees free education, school equipment for first-year pupils, and clothes for needy children. Additionally, firms contribute a 40 percent social insurance tax towards the state's welfare and unemployment programs. While government allocations increasingly favor the vulnerable, the wealthy clients are referred to self-financed services and institutions. In this way, government expenditure targets the rich to provide cash assistance, family allowance, and selected consumer subsidies for the poor.

Housing

Before the Russians came to Central Asia, the Tajiks were the predominantly settled population of the region that is Uzbekistan today. They had built their urban centers in Samarqand and Bukhara and had gained prominence for their role as intermediary between China and Europe for trade on the Silk Route.

|

Before the advent of the Soviets, however, Uzbek Turks had joined the Tajiks, creating a dual society. Tajiks and the Uzbek ruling class lived in the cities, while large Uzbek tribes nomadized in the countryside. Nomad Uzbeks lived in yurts or yurtas, round, portable tents that can be dismantled in minutes and reassembled within an hour or so. During the Soviet era, the government provided rent-free apartment blocks for everyone. The nomads, except for herders, were all settled so that they could be controlled and accounted for. Today, most Uzbeks own their own houses. Some belong to the Partnership of Houseowners. Even though construction materials are hard to get, and the prices high, some venture into building new houses or remodeling the old. Since independence, one million Uzbek families have become owners of previously state-owned apartments and 700,000 families have moved into privately owned dwellings. Utilities throughout the republic remain under state control. |

|

Religion The Uzbeks are predominantly (88 percent) Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi School. A great number, however, especially in the Ferghana Valley, practice Wahhabism, a sect that is based on the strictest of all the schools of Islamic law, the Hanbaliyyah School. Conservative to the core, the Hanbalis follow the letter of the Qur'an. Funds for the education of the Wahhabi Uzbeks come from Saudi Arabia, as do the teachers and trainers who expand the faith not only in the Ferghana Valley but in Kyrgyzstan (Jalalabad, Osh) and Tajikistan (Qarategin, Qurqanteppe, Hissar) as well. There are also some (9 percent) Eastern Orthodox Christians and other (3 percent) religions, especially Jews. Language Uzbeki belongs to the Qarluq division of the Turkic branch of the Uralic/Altaic family of languages (cf., Kazakh and Kyrgyz of the Nogai division). Different Uzbek tribes--the dominant Qarluq or Chaqatai group, the Oguz, and the Qipchaq--speak their own dialects. As early as the 12th century, a literary language was established; that language, based on an Oguz dialect (i.e., Turkmen), continued until the 15th century, when the Uzbeks arrived on the scene. During the 15th century the Qarluq dialect was selected as the base for the literary language. This language, along with Tajiki, served the needs of the sarts until 1917. With the onset of Sovietization, the bilingual Uzbek sarts have become trilingual. They speak Russian (14.2 percent), as well as Tajiki (4.4 percent). 7.1 percent speak other languages. |  |

The Arabic-based script of the Uzbeks, too, underwent a number of changes. It was changed into Latin in 1928 and continued in that mode until 1940. The reason for the change was explained in the Arabic script's inability to accommodate the technological demands of the 20th century; rather than a need to distance the Uzbeks from their main source of spiritual sustenance, Islam. In 1940, the script was changed to Cyrillic. This time the reason was more direct. In as much as all Soviets would have to learn Russian, why not become familiar with the script from the very beginning? At the present, Uzbekistan is in the process of changing its script back into Latin. The process, which begins in kindergarten, is deemed the best way to familiarize the future youth of Uzbekistan with the new script. Whether Tashkent and other major cities implement the change in the same way that the provinces are, remains to be seen. Much of the official correspondence is still carried out in the Cyrillic script.

Government

The name of the country is the Republic of Uzbekistan. The capital of the republic is Tashkent. With a population of about 2,730,000, Tashkent is the largest city in Central Asia.

|

Government type: Uzbekistan is a republic with authoritarian presidential rule. Most of the power is placed in the executive branch . Administratively, the republic is divided into 12 provinces. Uzbekistan became Independent on September 1, 1991 and adopted a new Constitution on December 8, 1992. Uzbekistan’s legal system is based on the Soviet civil law with no independent judicial system. Suffrage is at 18 years of age. |  |

The government of Uzbekistan consists of three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The executive branch comprises a chief of state or president (elected by popular vote for a seven-year term), a head of government or Prime Minister, and a cabinet of Ministers who are appointed by the president with approval of the Supreme Assembly. The president also appoints the prime minister and deputy ministers.

The legislative branch consists of a unicameral Supreme Assembly (Oliy Majlis) with 250 seats. The members are elected by popular vote to serve five-year terms. In 2002, an amendment was added to the constitution according to which a second chamber will be established via elections in 2004.

The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court. Judges are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Supreme Assembly.

Political parties and leaders

Uzbekistan has a number of political parties including Adolat (Justice); the Social Democratic Party; the Democratic National Rebirth Party; the People's Democratic Party; and the Self-Sacrificers Party. There are also several Political pressure groups, chief among them are the Birlik Movement; the Erk Democratic Party; the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan; and the Independent Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan.

In recent Uzbek history, there have been a number of political uprisings, with the aim of shaking off the exploitative yoke of the Russians, and the Europeans in general. As early as 1924, 16,000 Uzbeks were purged in order to put an end to the Basmachi movement in Central Asia. A similar purge occurred in the mid-1930's to mop up, as it were, the Islamists and the nationalists.

The newest threat to the Republic comes from the regional Islamic Opposition centered in the Kofar Nihon region of Tajikistan and the Ferghana Valley of Uzbekistan. Led by long-time professionals like Himmatzoda and Namangani, the Opposition seeks to infiltrate Uzbek politics in the manner that it has Tajik politics and, in the process, undermine Uzbek authority. By holding Kyrgyz villagers hostage, they also intend to destabilize the rule of Akayev in Kyrgyzstan. After a decade of soul searching, the Central Asian republics are coming to an understanding that the Islamic threat to their European way of life comes from within themselves rather than from among "bad apples" in neighboring countries.

At the beginning of their journey to independence, the Uzbeks decided to create a moderate, democratic Islamic state; even though the designation "Islamic" was used to pay lip service to those who felt the seat of Islam in Asia must play host to the revival of the faith after seventy years of Soviet rule. They also intended to introduce a market economy through privatization, decrease the cotton monoculture, keep Russia moderately involved in Uzbek affairs, cooperate with the CIS, and decrease the hold of tribalism and the mafia on the State. Some of those goals have been achieved but some have spawned problems of their own.

| Ethnic strife, especially between the Uzbeks and the Tajiks over Samarqand and Bukhara, is another thorn in the side of Tashkent. Additionally, Tajikistan claims that resources on which Uzbekistan draws for most of its prosperity lie in the Surkhan Dariya region, an area in southeastern Uzbekistan still heavily populated by Tajiks. This latter statement, however, is a Tajik claim supported only by archival documents. But perhaps the most pressing problem of Uzbekistan is tribalism and the mafia. The latter has created a network that controls almost every facet of life. Even registration at a school or college has become a task, needing dollars to accomplish. Travelers in transit are stopped and fined by officials who refuse to issue a ticket for the fine they receive. |

Flag

| Adopted September 30, 1991 Three horizontal stripes: blue over white over green stripes are separated by red fimbriations on the blue stripe, at the upper hoist-side, are a white crescent moon and 12 stars arranged in rows of three, four, and five new moon stands for the rebirth of the nation and the 12 stars represent the signs of the zodiac. |

Democratization

General Introduction

In order to understand the economy of the republics of the former Soviet Union, it is necessary to understand how centrally controlled economies work and how a centrally controlled economy is changed into a market economy.

In simple terms, the Communist Manifesto gave birth to a number of economies in Central Asia all of which were controlled by the state. The articles of the Manifesto asked for a total, central control of all aspects of life. In other words, all the peoples’ assets were taken from them and placed under the supervision of the State. This included the factories, plants, and natural resources, as well as human resources.

Privatization is the reverse of centralization. It requires a centrally controlled state that wishes to become a modern independent state to decentralize its agriculture, industry, businesses, and housing. It requires that the individual be given the right to buy and sell property. Means of transportation, production, and communication should be placed in the hands of the people. Similarly, the state should decentralize its banks, allow foreign investment to help develop its resources, and become a party to local and international efforts in running a meaningful and profitable market economy.

A truly independent republic cannot ignore freedom. It must allow its population the right to free speech by placing the media (newspapers, radios, and televisions) in the private domain and by removing censorship. Additionally, people should be given political freedom so that they can form political parties, stand for election, and vote.

What was outlined above serves as the basis for creating a democratic state with a stable government. A republic with a parliament that respects international law and which legislates laws that are sensitive to ethnic, racial, ideological, national, and gender concerns of the people, a government that recognizes equal opportunity and equal rights of its people.

Finally, an independent state must create access to education and health care through state and private welfare programs, it should form committees to oversee its conduct of human rights, as well as a committee to handle abuse of natural resources.

Since receiving their independence, the republics in Central Asia have responded differently to the demands of independence, especially with respect to privatization, political freedom, and human rights issues. The difficulty does not rest with the republics as much as with the nature of changes that are required of them. Obviously these changes cannot be meaningfully implemented unless those receiving the changes are cognizant of the rules of democracy. As every one knows, the road to democracy is long. It requires sacrifice as well as a large amount of funds for educating the people and making them understand the working of the law vis-à-vis the rights of the individual and the community.

Economy

Uzbekistan's economy is primarily agricultural. However, the amount of cotton--one of the primary mainstays of the economy--is not as much as it was during Soviet times when Uzbekistan filled an annual quota of 10,000,000 tons. At the present, 4,000,000 tons a year is the norm. Furthermore, Uzbekistan is a major center for the cultivation of the silk worm. Additionally, Uzbekistan is rich in natural resources like petroleum, coal, natural gas, sulfur, chemicals, and copper; it has sufficient hydroelectric power (Farkhad dam on the Syr, 1948) to meet its own needs, and has an industrial base that can produce cotton harvesting machines, gins, and at least three models of private cars.

Most of the former republics of the Soviet Union, upon gaining independence, abandoned their command economies and joined the global free market. Uzbekistan did not. Rather, it modified the Soviet system to fit its new needs. In this, the Uzbeks followed the examples of the countries in Southeast Asia and China. Consequently, they replaced the monoculture economy imposed by the Soviets with a program of controlled diversification. Needless to say, by adopting this strategy, they rejected the system dictated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

In 1994, Uzbekistan adopted an "import substitution economy" plan. The format of the plan is simple. It requires Uzbekistan to select several economic sectors from among all the sectors that form its economy for rapid development. It does not matter, for instance, if the selected sectors, at the time of selection, are importing goods and services. Uzbek authorities chose the following six economic sectors: energy, food, machinery and equipment, chemicals, metallurgy, and textiles. It was decided that these sectors should receive sufficient government subsidies until their status is raised, both qualitatively and quantitatively, to self-sufficiency. Once that goal was achieved, those sectors were to join the exports sector.

At the beginning, even though Uzbekistan had indicated its intention to work outside the framework of the other republics, the IMF was hopeful of striking a deal. By 1996, however, it became apparent that Uzbekistan was not considering joining the global market as had the other republics. The IMF, therefore, suspended its $185 million standby loan arrangement with Uzbekistan, a move that forced the republic to rely entirely on the strength of its sum [soom]. What Uzbekistan had not foreseen was that a continued reliance on the sum distanced it from both the world markets and all potential foreign investors. By the end of the 1990s, the republic found itself incapable of developing most of its resources unless foreign investors were heavily involved in its economy. As a result of this realization, the economy of the republic underwent drastic structural changes.

The Uzbeks’ strategy that led them into this gamble with their economy was typical of some decisions made in the region. They assumed that by offering incentives, the investors would agree to join the republic's market on Uzbekistan's terms. They were wrong. In the following years, the Uzbeks implemented a series of reforms. They improved their judicial system and its modes of implementation, expanded privatization, removed barriers to foreign investment, reduced bureaucracy, stabilized the sum, liberalized prices, and agreed to comply with both the World Bank and the IMF guidelines. Additionally, they adopted a foreign investment code and expanded foreign investor privileges, insurance, and protection. By 2001, it was no longer necessary to coax Uzbekistan to join the global market, it gave in by itself to a genuine economic reform. Furthermore, the republic sought assistance and advice from the IMF, as well as from the other financial institutions.

Uzbekistan's economy is susceptible to the rise and fall of the price of cotton. To diversify, the government has introduced the production of wheat, barley, and rice. But these crops have created economic problems of their own, in some places forcing the government to import food. In spite of the many river valleys in which to cultivate cotton and other crops, the Uzbeks have been forced to add numerous man-made canals to irrigate fields carved out of the desert. This method of irrigation has put a heavy strain on the Aral Sea, normally partially replenished by the Amu Dariya. Neither is Uzbekistan able to reverse the process and allow the Amu to feed the Aral. Farming in dense agricultural regions like the Ferghana Valley employs 44 percent of the labor force and feeds a large percentage of the population.

Uzbekistan’s labor force is estimated at 11.9 million. The labor force by occupation is divided as follows: agriculture 44 percent, industry 20 percent , and services 36 percent. The unemployment rate is 10 percent and the underemployed rate is 20 percent . Uzbekistan’s revenue is $4 billion and its expenditure is $4.1 billion.

| Agriculture Although Uzbekistan appears to be a dry, landlocked country, it is blessed with an abundance of river valleys, a major asset when considering the amount of irrigation needed for Uzbekistan’s white gold, cotton. In addition to the ten million tons of cotton, which the republic produces annually, it also produces a rich and high-quality gold in its mines in the Muruntau region. |

Uzbekistan also owns one of the world's largest reserves of natural gas. As noted, Uzbekistan's economy draws on cotton, natural gas, hydroelectric energy, agricultural products other than cotton, like wheat and rice, as well as on animal husbandry.

About 88 percent of Uzbekistan is desert, steppe, and mountain, and only 11 percent is arable. Although the republic is rich in cotton and mineral resources including oil, natural gas, gold, nonferrous metals, copper, zinc, tungsten, silver, and lead, the republic's future rests in the ability to attract investors that would develop all its resources equally well. Furthermore, it must put the Soviet-imposed production of a limited number of commodities behind it.

Uzbekistan's economy is agricultural-based with cotton as its primary mainstay. Among the republics of the former Soviet Union, Uzbekistan is the fifth largest cotton grower and the second largest cotton exporter. It is also a major center for the cultivation of the silk worm. Uzbekistan's silk fabrics, among the best in the region, are marketed throughout Central Asia.

Following Soviet tradition, Uzbekistan has created a single Central Asian agro-industrial system in which hydroelectric and gas-based energy combine to meet the energy and other needs of a growing population. The hydroelectric stations on the Naryn, Chirchik, and Syr rivers contribute immensely to the production of fertilizers required by the chemical industry centered in the Namangan, Andijan, and Navoi regions. From the gas fields of these centers, and of the Qashqa Dariya region, Uzbekistan supplies Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan with natural gas. Uzbekistan's other agricultural products include rice, wheat, barley, grapes, pomegranates, melons, and various types of grains. Other sectors of the economy are livestock raising, especially the Astrakhan fur, cattle, sheep, pigs, and goats.

Industry

During World War II, as a part of the process of moving their factories East, the Soviets moved a large aircraft assembly plant to the Tashkent region near Chikolov. Uzbekistan's industry, however, was primarily centered on the needs of its agricultural sector, which, in the main, consisted of cotton.

| Three levels of industry are distinguished: light industry consisting of handicraft, leather products, and textiles, especially silk textiles; the food processing industry which is responsible for all kinds of canned foods and durable consumer goods; and heavy industry which consists of fuel, energy, metallurgy, machinery, chemicals, timber, and building materials. Petroleum, coal, natural gas, sulfur, chemicals, and copper are among Uzbekistan's other natural resources. |  |

Privatization

Uzbekistan does not have a good record of privatization. In fact, its privatization record is poor. By the mid-1990s, Uzbekistan had privatized some housing, some small concerns, and established mutual funds. The privatization of the republic's substantial enterprises remained promises. It should be noted that Uzbekistan's entry into the market was different from that of the other republics. One reason is that, at the time of its entrance, Uzbekistan already had a firm control over its resources. By the same token, of course, it could not develop the same abundant resources that it had preserved on its own. In fact, for some of those resources, it still remains dependent on imports.

Banking

Uzbekistan has 35 mostly state-owned commercial banks. Of these, the most important are the Uzbek Central Bank and the National Bank of Uzbekistan. All banks are authorized to make foreign exchange transactions. After the fall of the Soviet Union, unlike the other republics, Uzbekistan did not reform its banking system to comply with the international norms. As a result, the country's banking procedures became cumbersome. Depending on the type of transaction, there might be a delay of anywhere between two days and two months for a transaction to clear the bank.

Uzbekistan's currency, the sum [soom] was introduced on July 1, 1994. In 2002, one US dollar was worth 970 sums.

Exports and Imports

Before the fall of the Soviet Union, most of Uzbekistan’s trade was with the republics within the Union. After the fall, Uzbekistan chose to stay away from the free market and develop its own resources. Uzbekistan also decreased its dependency on other world markets by substituting its own poor goods for goods that it did not want to purchase at world market value. During the last decades of the 20th century, this process damaged the republics ability to attract investments needed for building the infrastructure necessary for developing its natural resources. In recent years, Uzbekistan accepted the shortcomings of its system and joined the world market.

Exports

Uzbekistan's export commodities include: cotton, cotton and silk fabrics, natural gas, machine tools, Nurata marble, Karakul pelts, gold, energy products, mineral fertilizers, ferrous metals, textiles, food products, and automobiles. Uzbekistan's export partners are Russia, Switzerland, UK, Ukraine, South Korea, and Kazakhstan. Uzbekistan's total exports in 2001 is estimated at $2.8 billion.

Imports

Uzbekistan's import commodities include: wool, wheat, machinery and equipment, foodstuffs, chemicals, and metals. Uzbekistan's import partners are Russia, South Korea, United States, Germany, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine. Uzbekistan's total imports in 2001 is estimated at $2.5 billion.

Balance of Payment

Uzbekistan's external debt was estimated at $5.1 billion in 2001. In the same year, Uzbekistan received approximately $150 million in economic aid from the US.

Internet

The Internet country code for Uzbekistan is .uz. There are 42 Internet Service Providers (with their own international channels) and about 100,000 Internet users.

Transportation

In 2000, Uzbekistan had a total of 3,656 km of common carrier service railways; a total of 81,600 km of highway, 71,237 km of which is paved. There are also 10,363 km of road on unstable earth, difficult to negotiate in wet weather. There is also 1100 km of waterway and 1100 km of pipeline for carrying crude and natural gas. As of 2001, there are 267 airports, 10 with paved runways.

Communication

In 1999, there were 1.98 million telephones and, in 2003, there were 130,000 mobile cellular telephones in use. The telephone system of the republic is antiquated and totally inadequate; only in Tashkent and Samarqand the domestic telephone system has been expanded and technologically improved. As of 1998, six cellular networks have been in operation: four GSM, one D-AMPS, and one AMPS. Uzbekistan is linked via landline or microwave radio relay with CIS member states and via leased connection through the Moscow international gateway switch to other countries. Uzbekistan's link to the Trans-Asia-Europe (TAE) fiber-optic cable makes it independent of Russia.

Military

The Uzbek military is composed of an army, air and air defense forces, National Guard, and security forces. The latter includes both internal security and border troops. In Uzbekistan, Military age is 18. Available military manpower is 6,940,031. Military manpower fit for military service is 5,635,099. Uzbekistan’s annual military expenditure is about $200 million.

Border Issues

When the republics were created, a major problem to resolve was the division of the rivers so that all republics could make meaningful use of water resources for their assigned agricultural tasks. At that time, since all the republics were within the same Soviet nation, there were no disputes. After the fall of the Soviet Union, however, individual republics have tried to use the water that crosses their territory to their own advantage by building additional dams and canals. And that has made water-sharing an issue. For instance, the prolonged regional drought in recent years has created water-sharing difficulties for Amu Dariya river states, leading to border clashes. At the present, Uzbekistan has border disputes with Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. The delimitation with Kazakhstan is complete, waiting demarcation. But the situation with Kyrgyzstan has become complicated because of Uzbek enclaves. Uzbekistan's border situation with Tajikistan is being discussed.

Like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan is a transit country for Afghan narcotics bound for the Russian and Western European markets. The republic illicitly cultivates a limited amount of cannabis and small amounts of opium poppy for domestic consumption.