David Bell Birney, son of antislavery leader James Gillespie Birney, was born: May 29, 1825, in Huntsville Alabama. His family moved to Cincinnati, where his father published a newspaper, when the David was thirteen years old. They then moved to Michigan and finally to Philadelphia. After graduation from Andover, young Birney entered business, studied law, and was admitted to the bar. On October 31, 1850, Brimley was initiated in Franklin Lodge, #134, in Philadelphia. No other information was located listing further degrees. In Philadelphia, David Birney was active in business, and practiced law from 1856 until the outbreak of the Civil War, meanwhile studying military subjects which equipped him better professionally than most volunteer officers mustered into service. He was a very successful lawyer and businessman, well respected among high circles within the City of Philadelphia

Birney recruited the 23d Pennsylvania largely at his own expense and began as Lieutenant Colonel of that infantry unit, a 90-day militia regiment which muster in on 21 April 1861 and mustered out on 31 July 1861. His unit became a three-year regiment on 31 August 1861 and he was commissioned its Colonel from that date, due to the illness of Col. Charles P Dare who would later that year pass away. He led the 23rd PA at Falling Waters and the occupation of Winchester. On 17 February 1862 he became Brigadier General of Volunteers. Birney's first important field command was as commander of the 2d Brigade, 3d Division (Kearny), III Corps (Heintzelman), which he led through the Peninsular campaign. He was court-martialed and acquitted of "halting his command a mile from the enemy" as alleged by Brigadier General Samuel P. Heintzelman at the battle of Fair Oaks (Seven Pines). General Birney was later cleared of all charges and restored to command, continuing to lead his brigade through the 2d Bull Run campaign, taking temporary command of the division after Major General Philip Kearny was killed at Chantilly on September 1st 1862 while supporting Major General John Pope's Army of Virginia's flight from the field at Manassas.

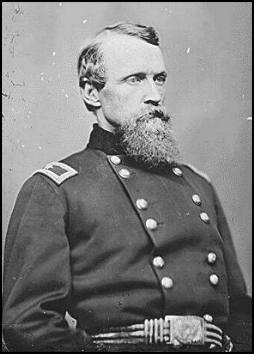

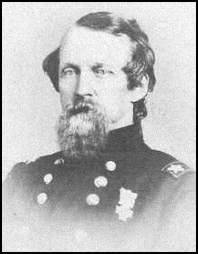

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

Succeeding General Kearny in command of the division, General Birney served with distinction with the Army of the Potomac commanding the 1st Division, III Corps (Stoneman) at Fredericksburg where he was again charged with dereliction of duty. However, the charge was not substantiated and Birney was, in fact, highly praised by his Corps commander, Major General George Stoneman. Birney was promoted to Major General to rank from 20 May 1863, for his able leadership at Chancellorsville where he command the 1st Division of the III Corps (Sickles). Despite two slight wounds himself, General Birney commanded the III Corps at Gettysburg after the wounding of Major General Daniel E. Sickles on 02 July 1863, retaining command until February 1864.

At Gettysburg, Birney received his marching orders in Emmitsburg in mid-afternoon on July 1 and made a three hour march to Gettysburg. At dusk, with two brigades of his division, he arrived and went into camp on Cemetery Ridge, just north of Little Round Top. The third brigade, Col. Regis de Trobriand's, arrived at 10:00 A.M. on July 2, and Birney's division went into position along Cemetery Ridge with its left resting on Little Round Top, facing west; Birney's men represented the far left of the Army of the Potomac. At 11:00 A.M. Birney sent out a detachment to scout the woods on Seminary Ridge to the west. They found the woods swarming with Confederates. This convinced corps commander Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles that he was about to be attacked, and provoked his decision in mid-afternoon to move the entire Third Corps forward nearly a mile to higher ground on the Emmitsburg Road. Once advanced, Birney found himself with the responsibility of holding the front from the Peach Orchard back to Little Round Top. There were two immediate problems with the new position. First, he didn't have enough men to cover that distance. Second, whomever he put at the Peach Orchard would be exposed in a salient which could be overwhelmed by two directions, west and south, with woods only a few hundred yards away that hid the approaches in the direction of the enemy.

About 4:30 that afternoon, Hood's entire Confederate division fell on Birney's line shortly after his men had taken their new positions. The far left of the line at Devil's Den was immediately in danger of being overwhelmed. Little Round Top--the key to the Union defense because it was an ideal artillery platform that looked down on the entire Union line--was to the left of Devil's Den, and Birney hadn't posted any defenders there at all. While Sickles sent for help, Birney used the regiments of de Trobriand's brigade in the middle of his line to shore up the ends at the Peach Orchard and Devil's Den. This arrangement made for a weak defense--the regiments Birney cannibalized from de Trobriand and parceled out on an emergency basis too often arrived on unfamiliar ground, with no time to get set before the Rebels came in with a whoop. Also, once let loose, these individual regiments many times stayed out of reach. Coordination became impossible. Birney began to give orders to any units in the vicinity, whether or not they were under his authority. His interference created additional coordination problems for the Fifth and Second Corps units rushing over to help.

Birney's Headquarters 1864

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

Birney Post #63

(Click to Enlarge)

|

The 3,000 Rebels in Barksdale's and Wofford's brigades boiled out of the woods around 5:30, overrunning the Peach Orchard. When Sickles went off the field with his leg mangled by a cannonball just afterward, he passed the Third Corps command to Birney at the worst possible minute. Birney's own division was already fleeing the field, and Humphrey’s division was fighting for its life to the north. A short while later, when army commander Maj. Gen. George Meade learned that Sickles had been taken off the field on a stretcher, he extended Second Corps commander Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock's authority to include the Third Corps. Birney’s part in the battle was effectively ended.

As Birney watched the few survivors of his division gather about him in the twilight, he whispered to one of his lieutenants, "I wish I were already dead." That night at the meeting of generals at Meade's headquarters, Birney said he considered the Third Corps "used up" and the army unlikely to be able stay and fight. He was a defeated man. The remnants of the Third Corps were placed behind Cemetery Ridge and were not used on July 3.

David Birney cut an uninspiring figure. "He reminds me of a graven image," wrote one of his men, "and could act as a bust for his own tomb, being utterly destitute of color." He was "as expressionless as Dutch cheese." Theodore Lyman of Meade's staff wrote later of Birney….. "He was a pale, Puritanical figure, with a demeanor of unmovable coldness; only he would smile politely when you spoke to him. He was spare in person, with a thin face, light-blue eye, and sandy hair. As a General he took very good care of his Staff and saw they got due promotion. He was a man, too, who looked out for his own interests sharply and knew the mainspring of military advancement. His unpopularity among some persons arose partly from his own promotion, which, however, he deserved, and partly from his cold covert manner."

According to artillerist Col. Charles Wainright's account of Birney's procession through Frederick, Maryland on the march north to Gettysburg, when Birney was acting corps commander in Sickles absence, Birney showed himself in love with the trappings of military life: First came a line or two of mounted cavalrymen with drawn sabers, then a band, then General Birney, followed by his staff in a neat formation, and finally the Third Corps. Birney's little parade gave all the officers something to gossip about, and prompted Wainright to comment that "he certainly means to have all the 'pomp and circumstance of war' he can get. Such feats are not common in this army, and do not take." With all Birney's coldness and pomposity, however, he was in fact a capable leader of men. Lyman was very clear about that. "In my belief," he wrote, "we had few officers who could command 10,000 men as well as he. . . . I always felt safe when he had the division; it was always well put in and safely handled." The thirty-eight-year-old Birney was born to a famous father. David was the son of James B. Birney, a Kentuckian who had once owned slaves but who had become one of the country's most vehement abolitionists, running twice for President on the Liberty Party ticket, a man with an international reputation at a time when slavery was a burning issue in the Western world. David attended Andover Academy, studied law in Cincinnati, and practiced law in Philadelphia. By the time of the outbreak of the war he had a very successful practice with many influential friends.

Lt. Col. Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

General David Bell Birney

(Click to Enlarge)

|

Birney foresaw the coming of the Civil War, and in 1860 he began an intensive study of military subjects and got an appointment as lieutenant colonel of a regiment of Pennsylvania militia. With this meager preparation, when the War began he received appointments to colonel of the 23rd Pennsylvania (August 1861) and brigadier general (February 1862) in quick succession, promotions which were too early for a novice and which spawned much envy. Though these appointments were pure politics, he proved to be competent and dependable in command. He first commanded his Third Corps brigade (Ward's brigade by the time of Gettysburg) at Seven Pines, where he was removed from command owing to a misunderstanding during the heavy fighting on the first day. Cleared of charges of disobedience, (and commended by fiery division commander Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny), he was restored to duty in time for the Seven Days a month later, where his brigade repulsed superior numbers at Glendale. Kearny again praised Birney, this time for his "coolness and judicious arrangements" after the latter battle. At Second Bull Run, Birney's brigade lost over six hundred men in intense fighting. Two days later, he replaced the irreplaceable Phil Kearny in command of the division when Kearny was killed at Chantilly on September 1, 1862.

Stationed in Washington, he missed Antietam, but Birney's division was back with the army at Fredericksburg. There, he again got in trouble, this time for allegedly balking when being asked to support Meade's division's attack (oddly, he was complimented in corps commander Brig. Gen. George Stoneman's official report for "the handsome manner in which he handled his division" on that same day). Birney led his brigades in extremely heavy fighting at Chancellorsville, where his division lost a horrendous 1,607 casualties, more than any other division in the army. As a result of his distinguished service in that battle, received a promotion to major general on May 20, little more than a month before Gettysburg. Birney, despite being a "political general" with a lack of military training, was a seasoned division commander by the summer of 1863. Having led his division in action in two battles, familiar with it since its inception in early 1862. If he was not dashing, at least he was thorough and capable.

However questionable his performance in the most crucial battle of the war, nobody could argue Birney's political connections, and he remained at the head of the decimated Third Corps through the fall campaigns and into 1864. In the spring reorganization of the army, the corps was broken up and Birney was reduced in the army hierarchy, replacing Alexander Hays at the head of the Third Division, Second Corps. General Birney took part in the Overland campaign and on 23 July 1864, was selected by Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant to command the X Corps. However, Birney fell ill with a virulent species of malaria, was ordered home, and died in Philadelphia on October 18th 1864, at age 39. He was buried in Woodlands Cemetery. He is buried there in Section 6.6 Lt 52 Grave 1, Next to his wife and with several other members of his family.

Birney Park, Phila

Former site of Birney Post

(Click to Enlarge)

|

Birney Park, Phila

Former site of Birney Post

(Click to Enlarge)

|

David Bell Birney / John Fassit and Staff

(Click to Enlarge)

|

Birney and staff

(owners of home on porch)

7/17/1864

|

Credits

The information to put this write-up together was taken from the following sources:

“Life of the 23rd Pennsylvania “Birney’s Zouaves” ,William J. Wray 1904, 1999,2004

“Life of David Bell Birney" Davis 1867

"Philadelphia and The Civil War" Frank Taylor

Research and Studies of Frank P. Marrone Jr.